By Bascomb James. Sailors and pirates—“Arrr!”—are a natural pairing in many swashbuckling adventure stories. Traditional sea pirate stories were often inspired by the European merchant trade with the East and Spanish trade with the New World. During the 18th century, it took about six months for a merchant ship to travel from London to Calcutta via the Cape of Good Hope. Cargos therefore, had to be durable, portable, and valuable. Valuable cargos in heavily-laden, slow-moving cargo ships were a favorite prey of pirates and other brigands. Pirates and pirate stories made an easy transition to the emerging science fiction market, appearing in juvenile and adult science fiction stories. We saw pirates in the movies, on television, and in our SF literature. It did not matter if the protagonist was a pirate or fighting pirates, we always knew there would be a chase, a heroic struggle, and at the end, we would share the winner’s exultation. Author David Wesley Hill delivers space pirates—“Jasper takes what Jasper wants”—as well as a hard science take on physics of planetary travel among the rings of Saturn. David Wesley Hill is an award-winning writer with more than thirty stories published in the U.S. and internationally. In 1997 he was presented with the Golden Bridge award at the International Conference on Science Fiction in Beijing, and in 1999 he placed second in the Writers of the Future contest. In 2007, 2009, and 2011 Mr. Hill was awarded residencies at the Blue Mountain Center, a writers and artists retreat in the Adirondacks. Saturn Slingshot by David Wesley Hill (Opening) Serendipity was an old ship. For more than two centuries she had sailed the same slow course from the inner planets to the Jovian moons and out toward the Kuiper Belt, that clot of comets lying between Neptune and Pluto. There, after unloading cargo and picking up freight bound sunward, her crew would adjust Serendipity’s sail, align the spinning prismatic circle of Kapton19(tm) at an angle to the distant solar orb, and begin the decade-long spiral back toward the heart of the system. Serendipity had made eleven such round-trip voyages. Like most of the crew Captain D’Angelo Jones had been born aboard her and had grown up within her slowly rotating tangle of corridors, cargo pods, and superstructure. Except for a brief period off wiving while Serendipity tacked above the Mars ecliptic to avoid the asteroid belt, Jones had spent his life inside the ancient vessel, and he knew her every sound, her every twitch and tremble, as well as he knew his own physical body. That long bass thrum was the tension of the vast sail against its rigging. The sad creaking pulsing in and out of audibility—that came from winches making microscopic alterations to the sail’s trim, keeping Serendipity bearing straight, propelled by sunlight across the ocean of night.

His mother’s cousin Leticia—Letty—was the lookout on watch. Her short black hair fanned in a curly halo around her dark features in the microgravity as her fingers flickered over the flat screen before her, scouring space aroundSerendipity with optical scanners and radar. “Everything’s clean for fifteen hundred klicks,” she said. “Leshawn?” D’Angelo asked. His niece’s second husband was at the weapons console. “Fore and aft cannons loaded with buckshot, D’Angelo. Lasers ready.” Beatrice had the helm. Unlike the others, Jones’s wife was fair, with a complexion the color of milk and a ruff of hair as golden as corn. Her eyes were pale, pale blue. Beatrice had been born on Phobos, which had been settled by Europeans. “Orbital insertion in six minutes, two seconds,” she said. “Hold her steady.” They were skimming seventeen hundred kilometers above the rings of Saturn, a vast uneasy ocean that stretched below them into infinity. Rivers of color, glinting silver and gold and crimson and umber, writhed into view and disappeared astern. Saturn was off the starboard bow. Although it was still a hundred thousand kilometers distant, the immense brown and yellow hemisphere subtended a quarter of the sky. Serendipity would approach Saturn within eighteen thousand klicks, entering a shallow orbit meant to fling her away into space like a stone from a slingshot. Only by leveraging such a gravitational assist from the gas giant could they hope to reach the Kuiper Belt. The efficiency of a solar sail was, unfortunately, directly proportional to its distance from the sun. “Whole lot of debris ahead, D’Angelo.” Letty studied her console. “Pebbles. A dozen pieces a meter in diameter.” “Range one thousand, two hundred eighty klicks,” Leshawn said. “Locked on and standing by.” “Clear a path,” Jones ordered. The rings of Saturn were composed of rock, dirt, and ice, trillions upon trillions of pieces varying in size from particles of smoke to floating mountains. Most fell toward the low end of this spectrum. The rings surrounded the planet in a belt almost three hundred thousand kilometers in diameter yet they had an average thickness of a single kilometer and sometimes their width could be measured in hundreds of meters. Occasionally, however, plumes of debris would be knocked out of the rings, either by collision with other particles or simply through some peculiarity of gravitational interaction. This created navigational hazards for ships approaching the planet. Leshawn triggered his weapons. Beams of coherent light lanced out. The debris in their path exploded into mist. “All clear,” he said. “Beatrice?” Jones asked. “Orbital insertion in four minutes, thirty seconds.” “Steady as she goes.” Jones gazed warily through the clear dome of the bridge out at the kilometers of sail, brilliant against the jet backdrop of space. Rock, dirt, and ice weren’t the only perils facing the old ship during its traverse of Saturn. The rings were inhabited by tribes of piratical aborigines, the descendents of castaways, outcasts, and criminals, who enjoyed nothing better than hijacking passing solar sails, robbing them of cargo, and enslaving the passengers and crew. These vermin lived in caves that they hollowed out in larger pieces of ring material. They mined iron, copper, lead, and other metals from the infinite expanse of detritus and refined the ore by hand, casting it into the machinery necessary to survive in vacuum. They breathed oxygen extracted from water ice through electrolysis, which also provided hydrogen to fuel their rockets. Since the sun at this distance was too feeble to support plant growth, they polished acres of ice to reflective smoothness, aligned these mirrors in huge fields, and concentrated the sunlight to an intensity sufficient for hydroculture. Even so protein was scarce in the rings. That was another reason the scum took captives. Unfortunately, despite their primitive level of technology, the aborigines were a real danger. Read the full story in Far Orbit: Speculative Space Adventures

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

World Weaver PressPublishing fantasy, paranormal, and science fiction. Archives

February 2024

|

- Home

-

Books

-

All Books

>

- Beyond the Glass Slipper

- Bite Somebody

- Bite Somebody Else

- Black Pearl Dreaming

- Cassandra Complex

- Causality Loop

- Clockwork, Curses, and Coal

- Continuum

- Corvidae

- Cursed: Wickedly Fun Stories

- Dream Eater

- Equus

- Fae

- Falling of the Moon

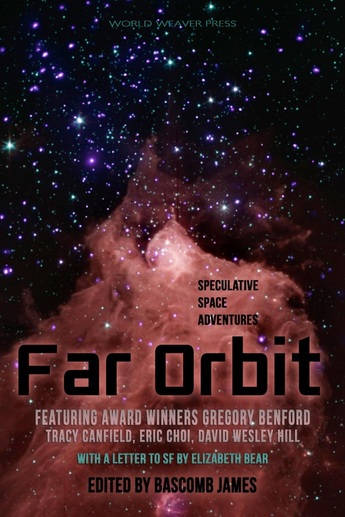

- Far Orbit

- Far Orbit Apogee

- Fractured Days

- Frozen Fairy Tales

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Winters

- Grandmother Paradox

- Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline

- Haunted Housewives

- Heir to the Lamp

- He Sees You When He's Creepin': Tales of Krampus

- Into the Moonless Night

- Jack Jetstark's Intergalactic Freakshow

- King of Ash and Bones (ebook)

- Krampusnacht

- Last Dream of Her Mortal Soul

- Meddlers of Moonshine

- Mothers of Enchantment

- Mrs Claus

- Multispecies Cities

- Murder in the Generative Kitchen

- Recognize Fascism

- Scarecrow

- Sirens

- Shards of History

- Shattered Fates

- Skull and Pestle

- Solarpunk (Translation)

- Solarpunk Creatures

- Solomon's Bell

- SonofaWitch!

- Speculative Story Bites

- Trenchcoats, Towers, and Trolls

- Weredog Whisperer

- Wolves and Witches

- Anthologies and Collections

- Novels

- Novellas

- Fairy Tale

- Fantasy

- Romance

- Science Fiction

- Urban/Contemporary Fantasy

- Young Adult SFF

-

All Books

>

- Blog

- About

- Contact

- Press / Publicity

- Newsletter Signup

- Privacy Policy

- Store

RSS Feed

RSS Feed