Guest Blog by Joseph F. Nacino The many islands of the Philippines have always been bountiful—bounded with deep waters full of fish, verdant with vegetation, and blessed with rich soil. But it’s also constantly wracked by natural disasters year after year, ranging from seasonal typhoons to the occasional fitful volcanos and rumbling earthquakes. This is because the Philippines is located both along the Ring of Fire—an area in the Pacific region where many volcanic eruptions and earthquakes happen—as well as the typhoon belt. Yearly, the country is hit by around 80 typhoons that develop over the tropical waters. Nineteen of these enter the Philippine region, and 6-9 of them make landfall. These all leave their mark, either people dead or severely affecting the infrastructure and economy. In 2020 alone, aside from the COVID-19 pandemic, the Philippines started off the year with the eruption of the Taal Volcano that caused heavy ashfall in the nearby provinces—including the capital, Metro Manila. In August, a 6.6-magnitude earthquake hit one of the country’s provinces. Out of the 20 tropical cyclones that entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility, 12 made landfall.  Photo: Eoghan Rice - Trócaire / Caritas Photo: Eoghan Rice - Trócaire / Caritas Climate change has also affected the Philippines in terms of severity and frequency of natural disasters, with El Niño causing drought and stronger storms. For the latter, consider Typhoon Haiyan (known locally as Supertyphoon Yolanda) in 2013 that killed at least 6,000. Rising sea levels are also expected to affect the country (more of this later). That’s why when I first heard about the solarpunk anthology being created by World Weaver Press about stories of multispecies cities, preferably set in the Asia-Pacific region, I was stumped in coming up with an idea for this. Creating stories set in the Philippines related to the natural environment and climate change isn’t a problem for me. What took me awhile to think about was the fact that since this was a solarpunk anthology, I had to come up with a more “hopeful” story than what I was used to. After all, year after year, after every disaster, the Philippines has to implement recovery and rehabilitation efforts, but it hasn’t made as many strides in implementing disaster risk reduction planning and activities. What’s more, we’ve been slow to integrate these with climate change adaptation and sustainable development policies.  Photo: AusAID Photo: AusAID In 2009, Typhoon Ketsana—known locally as Tropical Storm Ondoy—paralyzed Metro Manila with flash floods caused by heavy rainfall of 17.9 inches (455 millimetres) in just one day. Because of this, open-sourced flood maps detailing possible danger areas like Project Noah were later used by the government as part of their disaster risk reduction efforts. (Sadly, this was later defunded, and reverted back to the academe and private sector groups for their use.) So yes, we sometimes learn—but always at a cost. And given the track record of the national government, any efforts to address would be probably too little, too late. Given this overall situation, how could I write a story about hope? With “Mariposa Awakening,” I had to include all these elements. The main problem faced by the protagonists (and the country) in the story is the rising sea levels in the future. By 2100, projections of sea level rise would range from two to four meters, with 1.5 million people in the coastal and low-lying areas of the country being affected. This meant that whatever hopeful solution that could address this would be too late—the barn door was already open and the horse had already fled. That’s when I thought that this story doesn’t end after the natural disaster happens. No, this story begins after the disaster, with the country slowly slipping under the sea waters. That’s where this story begins, and what happens next is what we usually do here in the Philippines: we survive, we rebuild, and we try to find hope to give to the next generation of Filipinos. That’s the hopeful part of this story. Joseph F. Nacino writes for a living. He also writes stories that have been published in international (Fantasy Magazine, City in the Ice, Kitaab’s Asian Speculative Fiction) and local publications (the Philippine Speculative Fiction series, A Time of Dragons, Friendzones, etc.). Likewise, he’s helmed three anthologies featuring fantasy, science fiction, and horror in the Philippines published online, and in print and ebook form.

0 Comments

Guest Blog by N. R. M. Roshak In January 1994, a 6.7-magnitude earthquake shook Los Angeles. The Northridge earthquake rumbled through at 4:30 AM, waking residents and taking out the power grid. People poured out of their homes and into the darkened streets. And some of them dialed 911, not about the earthquake, but about what they saw in the dark sky: a strange “giant, silvery cloud” arching over the stricken city. That mysterious cloud? It was the Milky Way. The LA residents who called 911 on the Milky Way had likely never seen it before. LA's light pollution is notorious. Light spilling into the sky from streelights, buildings, signs, and searchlights is refracted by the coastal haze, creating an intense skyglow. LA's skyglow is particularly intense--pilots say they can see it from 200 miles away. The sky's brightest stars are barely visible, let alone the Milky Way. And LA isn't the only city affected. Most urban residents have trouble seeing the stars. This picture shows the constellation Orion, seen from the countryside and seen from the city. Unfortunately, the glow of light pollution has worse consequences than shutting humans off from the stars. Many animals' biology and lives are thrown off by nighttime lighting. And it doesn't take a city as bright as LA to affect them. Brightly-lit towers and tall buildings can confuse migratory birds so badly that they circle the towers until they collapse from exhaustion. Lights disrupt frogs' nighttime croaking. Baby sea turtles, who hatch on beaches, instinctively turn toward light to find the ocean--a strategy that worked for millions of years, when the sky over the open ocean was brighter than the land's shadow, but that fails when the land is topped with a city's glow. And this is only the tip of the iceberg. Dozens of species of mammals , reptiles , amphibians, insects, and even aquatic species like coral are affected by our cities' light pollution. These two consequences of urban skyglow — humans blinded to the stars, animals led astray — come together in my story for Multispecies Cities, "By The Light of the Stars". It's a gently speculative queer romance about turtle hatchlings who need a little help to find the ocean, and a human who needs a little help to believe in the stars. Writing this story opened my eyes to the effects of light pollution on all of us, human and animal. And it pains me that I can't show my own kid the stars from our urban home. If you have a kid that you'd like to share the stars with, I invite you to check out the free STEAM activities and readings on my blog: http://nrmroshak.com/how-many-stars-do-you-see-at-night/ And, if you're interested in learning more about light pollution, https://www.darksky.org is a good place to start. The characters in my story find a speculative solution to the turtles' problem; we can't do that in real life, but we can advocate for less light pollution and darker skies in our cities, for the sake of our turtles, birds, bats, frogs, corals, etc. and for ourselves. N. R. M. Roshak writes all manner of things, including (but not limited to) short fiction, kidlit, non-fiction and translation. Her short fiction has appeared in Flash Fiction Online, On Spec, Daily Science Fiction, Future Science Fiction Digest, and elsewhere, and was awarded a quarterly Writers of the Future prize. She studied philosophy and mathematics at Harvard; has written code and wrangled databases for dot-coms, Harvard, and a Fortune 500 company; and has blogged for a Fortune 500 company and written over 100 technical articles. She shares her Canadian home with a small family and a revolving menagerie of Things In Jars. You can find more of her work at http://nrmroshak.com, and follow her on Twitter at @nroshak.

Guest Blog by Phoebe Wagner In my short story “Children of Asphalt,” I used first person plural—“we”—as the point of view. This POV can be rather tricky as it includes the reader in that plural “we,” asking the reader to essentially join that community. Readers in the US will probably have read or heard of William Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily,” which is about a town grappling with the behaviors of a resident. This point of view is ideal for certain story structures, particularly ones that focus on an “other,” such as a stranger coming to town. I love trying less typical points of view, structures, plots, etc. in my writing, but so often, those stories end up being trunked because it becomes more about the technique and less about the characters. I struggle to find an atypical technique that speaks to the story, so I was excited when the voice of the community in “Children of Asphalt” came to me so clear. I’ve written pieces of solarpunk flash fiction in a similar first person plural POV because the group voice better encompasses a difference in narrative that I believe most solarpunk must strive for. Rather than individual responses to the climate crisis, I hope writers consider how communities respond instead. The climatic hero’s journey will not be the plot of surviving or adapting to climate change. One way to start changing the structure is to reconsider how writers create stories. For me, that was the POV. Even though it’s a community POV, I made the choice for there to be a difference in age, just as there might be with the reader. The “we” is the adults of the community, and the story would be entirely different if I’d chosen to write from the “we” of the children. I’m not sure I could write that story right now. The children of such a time will think so differently than I do that I wasn’t sure I could embody those ideas on the page in the short amount of space that I had. As the solarpunk genre continues to grow—and indeed, it does seem to be growing—I hope the writers consider the how of the story and not just the why. The climate crisis will become a narrative in the news, in history, and in art. In the US, with a focus on the singular hero so strongly embedded in white US literary heritage, solarpunk writers must consider how the shape and voice of a story can shift the focus from hero to community. Phoebe Wagner holds an MFA in Creative Writing and Environment and currently pursues her PhD in literature at University of Nevada, Reno. Her recent fiction can be read in Diabolical Plots, Cosmic Roots and Eldritch Shores and AURELIA LEO. In 2017, Upper Rubber Boot Books published her co-edited anthology Sunvault: Stories of Solarpunk & Eco-Speculation, and she’s under contract to co-edit another solarpunk book from West Virginia University Press. Currently, she blogs about speculative literature at the Hugo-finalist Nerds of a Feather, Flock Together and can be found online at phoebe-wagner.com.

Guest Blog by Amin Chehelnabi When I saw what happened in September 2019 to March 2020, I was overwhelmed by how much damage the bushfires had done to Australia as a nation. It was a period known as Black Summer, which was a very apt name, and a necessary one. Hundreds of homes were destroyed, not including the other buildings – business, industrial or otherwise – destroyed as well. In terms of surface area, hundreds of thousands of hectares was burned and over one billion animals were estimated to have died, and even some species were thought to have faced extinction. Here is a link to an article by the World Meteorological Organization with regard to Black Summer, for your perusal: https://public.wmo.int/en/media/news/australia-suffers-devastating-fires-after-hottest-driest-year-record. The damage Black Summer had done to the native wildlife of Australia was heartbreaking to me. Over ten thousand koalas were thought to have perished. Here’s the link to an article by ABC, which I recommend: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-02-18/ten-thousand-koalas-could-have-died-nsw-bushfires/11975378. When I had seen the damage the bush fires had done, a new kind of fire started in my heart. I could not ignore the desire to write something, anything, that would help me understand how such a thing was even possible, or that it even happened. So when I was invited to write for Multispecies Cities, I had the means to share a story that involved the consequences of how much we were damaging the climate globally. I wrote “Wandjina” with the intention of bringing awareness to what would happen if we ignored the damage being done to the world’s climate. I was also inspired by the activism of Greta Thunberg who had done her own work to tackle climate change, and someone who definitely has a fierce fire in her own heart. “Wandjina” is set in a future Australia where the bushfires are much, much worse than Black Summer. Working on this story required a lot of research, and I discovered information on how veterinarians and staffers at Zoos handle animals, including the proper way to hold certain native species so as not to injure them. Focusing on this element of caring for wildlife had given me a newfound knowledge about the responsibilities we have to take care of our world and of the creatures we share this world with. My main character is an Iranian woman called Tara who, feeling disillusioned by the governments’ lack of action to help the native species of Australia, took it upon herself to organize a crew to go and save these animals from certain death. If I were able to talk to Tara and ask her how she felt about it all, I wouldn’t doubt that she would be as fierce and as adamant as Greta holding up a sign outside the Swedish Parliament that read Skolstrejk för klimatet (School strike for climate). Because it’s a global issue regardless of whether we accept it or not, climate change can’t be ignored. Our feelings and opinions won’t change the inevitable conclusion that ignoring the damage done will do, and it’s up to all of us – in our own creative way – to help in making a difference and bringing awareness to others. Amin Chehelnabi is an Australian-born gay Iranian with a strong interest in the speculative fiction field. He has been a Collection/Anthology Judge for the Aurealis Awards, and a First Reader for Lightspeed Magazine. He’s also an alumnus of the Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Workshop at UC San Diego (2014), and a recipient of the Octavia E. Butler Scholarship Award. His publications include a horror story published with Innsmouth Free Press, which received an Honorable Mention in The Best Horror of the Year, Volume Seven (Edited by Ellen Datlow), and was a panelist for a three-day conference called Shaping Change: Remembering Octavia E. Butler through Archives, Art, and Worldmaking, which took place in 2016 at the Cross-Cultural Center at UC San Diego. He also has a Bachelor’s Degree in Fine Arts, majoring in sculpture, and loves cats.

Guest Blog by Vlad-Andrei Cucu ‘Man or woman? Black or white? Omnivore or vegetarian? All irrelevant now. They were taller than anyone on the street. Their soft and round flesh is hard and pointed steel. The last remnants of their face are two eyes, bright red light bulbs. They were stripped of human needs. They are now just another combat drone with a confusing code to tell them apart, XR1251T, codename "ElectroBody".’ This specific paragraph, albeit slightly awkward in its wording, is part of the seed that would later grow into the proper 'Iron Fox in the Marble City' story. Back in 2019, I took a class in creative writing at the university in Limerick, Ireland. Part of our assignment for the class was to write four different texts, and after writing mostly comedic stories for the first three, like a parody of ‘Dirty Harry’ style vigilante cops, or plot about Santa Claus meeting Dracula, I decided to finish off with a slightly more dramatic cyberpunk story, from which this paragraph came from. The full title was ‘Watch out! It’s ElectroBody’, and the plot was partially similar to the story I submitted to the ‘Multispecies City’ anthology, albeit presented from an outside point of view. However, I did not initially intend for the submission piece to end up as a sort of sequel, but instead it was an idea that developed along. When I first heard of the call for stories, I did not have any experience with the solarpunk genre, much less writing for it, but I wouldn’t end up anywhere without taking risks in art. So I wrote an initial draft while following some examples provided by Youtube videos and blog posts about solarpunk. The initial draft was terrible, bland and generally felt like it was the result of a corporate run computer told to generate a solarpunk plot. At the time, I held by it, but slowly realized how shallow it came across, so I scrapped it, but not without retaining some aspects. The major one would be the setting, as I initially chose Japan due to its frequent association with the cyberpunk genre, to which solarpunk was the antithesis. The dome garden in the story and the plot point of its protection were also there since this first draft. After some reconsidering, I was suggested by a friend who read both the first draft and the ElectroBody story to potentially combine the two. Surprisingly for a story set in Japan written from a western perspective, the only influence from anime and manga that came to mind was the visual design of Kithound, which I loosely based on the character Briareos Hecatonchires from the cyberpunk manga AppleSeed. I’ve never actually read AppleSeed so it didn’t carry any significant meaning, just thought it was a very visually striking design to work with. Of course, people are always invited to come up with their own imaginative designs while reading. From that point on, everything clicked into motion smoothly. I thought it would be a good idea to use an-ElectroBody like character, who would later become Kithound, as while they represented a lot of cyberpunk tropes that would contrast against the setting, it would also fit under the theme of multispecies in the anthology as the degree of technology implanted into such a person was so severe and drastic that the change essentially turned them into a new type of lifeform that would be neither machine or human, but instead a new species. Initially, it was going to be a standalone setting, before deciding to reuse the entire universe so I could add some nods to the original story, even if they might come across more as personal in-jokes, partially because it’s fun, but also because it’s interesting way of making the world sound bigger and more lively outside of the main narrative. This is also the reason why some things are not completely elaborated on, instead leaving a lot of ambiguity for the reader to imagine for themselves. The other aspect I retained was the main antagonist and their plan. Initially, the plot was going to slightly sillier and have more of a pulp comic vibe, with the major villain being a character called Baron Gold Blood, and the sub-plot of the captured animals was originally going to be the main focus that lead to the action-packed finale. Eventually Gold Blood got separated into the two characters of Mrs. Gulblut and Capital C, and everyone else was new to the second version. Of course, it didn’t just stop there. Something I learned about genre writing after being done with the new draft and during the editing phase was that an interesting way of writing is to start off by incorporating as many cliches and genre conventions as possible in an initial draft, and then look for the more generic or bland ones and see how they are integrated. Depending on whether they might be irrelevant or not, I either cut them out completely or tried to implement them in a more subtle way. One such instance was describing the city of Tokyo itself by directly referencing art nouveau in Kithound’s perspective, but later edited it down to actually describing those art nouveau elements. In the end, I’m very happy with how the result came to be, and I’m thankful for anyone that encouraged me with writing the plot, and Sarena Ulibarri and everyone else from World Weaver Press for the advice on editing the story, and I hope it proves to be an enjoyable read. Vlad-Andrei Cucu, by day an average student, by night an average student that expresses himself through drawing, indie game making, and more recently writing. Trained in the methods of anarchism in Romania’s mountains, and the art of creative writing in Ireland, he is eager to let out some weird, but interesting transhumanist ideas.

What happens when dolphins take over the world, and create a technology that humans have no understanding of? Author Shweta Taneja talks about her Multispecies Cities story, titled, "The Songs That Humanity Lost Reluctantly to Dolphins." Shweta Taneja is a bestselling author from India, most known for her fantasy series, Anantya Tantrist Mysteries. She’s a finalist in the prestigious French award Grand Prix de l’Imaginaire (2020) and was awarded the British Council Charles Wallace Writing Fellowship (2016). She is currently working on a book about scientists and an interplanetary adventure with an Asian ethos. She prolifically voices her passion for Asian, feminist and diverse fiction through her handle @shwetawrites. Find more at www.shwetawrites.com

Guest Blog by E.-H. Nießler There is something special about Solarpunk. It marries the fantastical with musings about 'what could be' in a way that used to be the sole domain of Science Fiction, back in the days when the genre was being defined. Yet it doesn't really concern itself with the insignificance of our existence on a cosmic scale or the horrors of an uncaring universe. It is more intimate than that. Unlike its grittier and disaffected sibling Cyberpunk, it doesn't lean into the nightmare our world becomes when we turn our human ingenuity against ourselves. It is more hopeful than that. When I started to write creatively in my youth, it was mostly when sad or angry. Writing made me feel grounded and happy when I was at my lowest. As a result much of what I produced was melancholic in nature. Systems were irrevocably broken, fate was unkind and destiny cruel. Still today I see these things in my work. I like a good tragedy, be it self-inflicted or force majeure. It's a disposition that I find easy to indulge. In 'Multispecies Cities' I was given the opportunity to make something different. The constraints of Solarpunk in general and the requirements of the anthology in particular made it easy to put aside my usual instincts and instead imagine a world where hardship is transient and misfortunes are stepping stones towards something better. A world where 'imagine what could be' sounds neither scary nor threatening. And I fell utterly in love with it. Perhaps it's just a personal thing. A question of where I am in my life right now. Or perhaps, and I have a slight suspicion it might be, the world in general is in a place where Solarpunk can truly come into its own. A genre in which we as readers and writers can be fantastical yet don't need to loose ourselves into fantasy. Instead we can fully acknowledge the challenges of our time like climate change, health, sustainability of our way of life, the manner in which we deal with the creatures with whom we share a planet. Yet at the same time it comes unburdened by defeatist cynicism or being ironic and aloof. There is a kernel of something precious in Solarpunk. A spirit of wonder like it can be found in the speculative fiction of old, but this time freed from the prejudices and injustices of the industrial and atomic ages. For me at least it has become near and dear to my heart, simply by asking the question: "What if we actually succeed? E.-H. Nießler is a freelance translator and writer from Berlin, Germany. Working as a retail-clerk, museum tour-guide and private tutor for the better part of two decades he managed to raise a family and obtain an MA in East-Asian Art-History and Japanese Studies from the Free University of Berlin in 2016. With his self published début novel Liminality — At the Edge of Worlds in 2019 he started to pursue his passion for writing in earnest. Find news about his work on www.atelier-vulpecula.com.

Guest Blog by D.A. Xiaolin Spires I’m sure many of us have come across seagulls flying across boardwalks, littering their droppings all over benches, railings, the ground, etc.. They’re scavenging for French fry remains, pecking at cardboard boxes or diving towards garbage cans. Some of these ‘pests’ even take food directly from people’s hands, engendering fits of alarm by unsuspecting meal-buyers about to take a bite… only to have their Philly cheese steak (or insert other food item here) snatched away from them! Seen as pests, seagulls scour the coasts for easy pickings. Their large numbers at such touristy spots belie the greater narrative of dwindling numbers of seabirds across the globe more generally. Given the seagull's ubiquity at touristy spots, soaring and diving for people's leftovers, it's possible that some people haven’t considered the wider notion of seabirds' roles in their ecosystems and the global impact of their decline. They deposit guano as a which helps cycle nutrients and organically fertilize marine habitats, including coral reefs. The stark reality of the decline of seabirds inspired this story. An academic article in Plos One described the near 70% decline of seabirds from 1950 to 2010. According to Audubon science, “two thirds of seabirds are at risk of extinction from climate change.” Despite the seagull’s bad reputation on board walks as a nuisance, seabirds more generally play a critical part in the marine ecosystem. Threats to seabirds include equipment left behind from the fishing industry, such as gillnets, longline hooks and trawling nets. In addition to getting ensnared in these ghost nets, seabirds also face another existential threat: starvation from disappearing food in the sea. With this dire data on hand regarding these majestic animals, a story began to form in my head. I thought about these soaring creatures and the adverse effect of human industrial activity on the wellbeing of these feathered fauna. I paired this line of thinking with a persistent idea of human-made art as evanescent and transient; something that would not endure over years and decades, but like all organisms, would decay and became part of the ecosystem itself. I was spending a good amount of time watching birds with some avid birders. Their keen interest in the welfare of various species and their attention to the details of the birds' varied social lives intrigued me. From these disparate but intersecting thoughts, the story "The Exuberant Vitality of Hatchling Habitats" was born. D.A. Xiaolin Spires steps into portals and reappears in sites such as Hawai‘i, NY, various parts of Asia and elsewhere, with her keyboard appendage attached. Her work appears or is forthcoming in publications such as Clarkesworld, Analog, Strange Horizons, Nature, Terraform, Uncanny, Fireside, Galaxy’s Edge, StarShipSofa, Andromeda Spaceways (Year’s Best Issue), Diabolical Plots, Factor Four, Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, Grievous Angel, Toasted Cake, Pantheon, Outlook Springs, ROBOT DINOSAURS, Shoreline of Infinity, LONTAR, Mithila Review, Reckoning, Issues in Earth Science, Liminality, Star*Line, Polu Texni, Eye to the Telescope, Liquid Imagination, Gathering Storm Magazine, Little Blue Marble, Story Seed Vault, and anthologies of the strange and beautiful: Deep Signal, Ride the Star Wind, Sharp and Sugar Tooth, Broad Knowledge, Future Visions and Battling in All Her Finery. Select stories can be read in German, Spanish, Vietnamese, Estonian and French translation. She can be found on Twitter: @spireswriter and on her website: daxiaolinspires.wordpress.com.

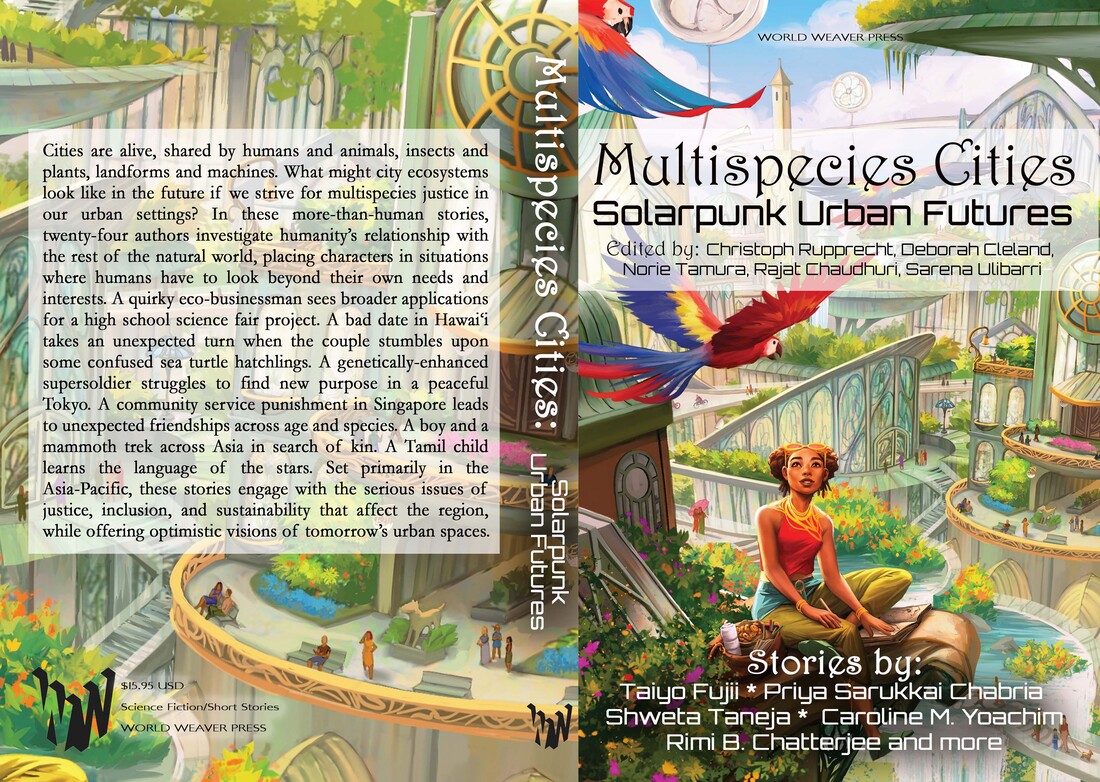

Multispecies Cities: Solarpunk Urban Futures is out in ebook and paperback now! This joint project between World Weaver Press and the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN) presents 24 stories that consider what city ecosystems might look like in the future if we strive for multispecies justice in our urban settings. Set primarily in the Asia-Pacific, these stories engage with the serious issues of justice, inclusion, and sustainability that affect the region, while offering optimistic visions of tomorrow's urban spaces. Anthologist Christoph Rupprecht is a researcher seeking to understand how stories might contribute to building better futures for humans and nature alike. There are links to two reader surveys in the book—please don't skip them! You can also find the pre-survey here (before you read), and the post-survey here (after you read the stories). "The 24 stories of this joyously ambitious solarpunk anthology chart a broad map for integrated relationships between humans and nature, spotlighting award-winning and emerging speculative fiction writers from Asia and the Pacific. The linguistically and culturally diverse lineup excels when entwining relational nuance with keenly handled futurist ideas." "Every story in this collection is a powerhouse, there’s not a weak one in the bunch. Written by Pan-Asian authors and set in locations from Northern China to Australia, each of these stories brings a new perspective and voice to the ideas of how we can better interact with our environment. Each has an overriding sense of hope that makes this collection a uniquely pleasurable reading experience." |

World Weaver PressPublishing fantasy, paranormal, and science fiction. Archives

February 2024

|

- Home

-

Books

-

All Books

>

- Beyond the Glass Slipper

- Bite Somebody

- Bite Somebody Else

- Black Pearl Dreaming

- Cassandra Complex

- Causality Loop

- Clockwork, Curses, and Coal

- Continuum

- Corvidae

- Cursed: Wickedly Fun Stories

- Dream Eater

- Equus

- Fae

- Falling of the Moon

- Far Orbit

- Far Orbit Apogee

- Fractured Days

- Frozen Fairy Tales

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Winters

- Grandmother Paradox

- Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline

- Haunted Housewives

- Heir to the Lamp

- He Sees You When He's Creepin': Tales of Krampus

- Into the Moonless Night

- Jack Jetstark's Intergalactic Freakshow

- King of Ash and Bones (ebook)

- Krampusnacht

- Last Dream of Her Mortal Soul

- Meddlers of Moonshine

- Mothers of Enchantment

- Mrs Claus

- Multispecies Cities

- Murder in the Generative Kitchen

- Recognize Fascism

- Scarecrow

- Sirens

- Shards of History

- Shattered Fates

- Skull and Pestle

- Solarpunk (Translation)

- Solarpunk Creatures

- Solomon's Bell

- SonofaWitch!

- Speculative Story Bites

- Trenchcoats, Towers, and Trolls

- Weredog Whisperer

- Wolves and Witches

- Anthologies and Collections

- Novels

- Novellas

- Fairy Tale

- Fantasy

- Romance

- Science Fiction

- Urban/Contemporary Fantasy

- Young Adult SFF

-

All Books

>

- Blog

- About

- Contact

- Press / Publicity

- Newsletter Signup

- Privacy Policy

- Store

RSS Feed

RSS Feed