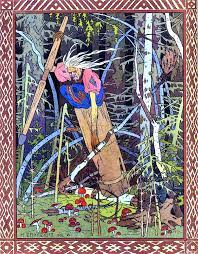

Guest Blog by Kelly Jarvis Every girl dreams of having a fairy godmother. But what happens when your fairy godmother is a witch? This is the question lurking behind my story for the Mothers of Enchantment: New Tales of Fairy Godmothers anthology. “A Story of Soil and Stardust” blends elements from traditional Cinderella and Vasilisa the Beautiful tales, casting Baba Yaga, the terrifying witch of Slavic folklore, in the fairy godmother role. I first learned about Baba Yaga through the anthology Skull and Pestle: New Tales of Baba Yaga. Described as a ferocious old woman with a hooked nose and long, bony legs, Baba Yaga can be found living deep in the woods in a broken-down hut that runs around on chicken feet. She flies through the air in a mortar and pestle, has a trio of horsemen to do her evil bidding, and satisfies her voracious appetite by devouring the flesh of children, adding their skulls and bones to the grisly fence that surrounds her forest property.  But, when we look beneath Baba Yaga’s frightening surface, we find so much more than a cannibalistic witch. She is a crafty crone, a wise woman, and an earth mother. Described as both a donor and a villain, Baba Yaga is just as likely to help the mortals she encounters as she is to eat them, and her insatiable hunger stands in bold opposition to the rules and restrictions imposed by civilized societies. Her name, which differs slightly within the Slavic languages, may reveal her softer side. “Baba” usually translates to “grandmother” or “old woman”, while “Yaga” may be a diminutive form of the name “Jadwiga”, a Slavic variation of the Germanic name “Hedwig”. Hedwig is also the name of the Catholic patron saint of orphans (Hedwig of Andechs), and although an exact connection between the saint and Baba Yaga can’t be drawn, the similarity of their names made me wonder how Baba Yaga might interact with the orphaned protagonists of Cinderella and Vasilisa tales. It was from this wondering that my witchy fairy godmother was born. Once Baba Yaga entered my story, the details of the narrative fell into place. The setting moved to the harsh northern forest. The pages filled themselves with warm baked breads, steaming bowls of porridge, grilled sausages, and thick pieces of gravied beef, offerings to satisfy Baba Yaga’s deep hunger. The doll, a symbol central to the Vasilisa tale, became a Matryoshka Doll, a set of wooden nesting dolls placed one inside the other. As a child, I delighted in twisting these dolls open to find smaller dolls inside, amazed by the number of unseen secrets the outermost doll could hold within her.  Stories are a lot like Matryoshka Dolls; they invite us to twist them open and find the treasures hidden within. Their smallest elements stand as reflections of the whole, and it can take time and patience to stack the pieces together in meaningful order. If a Matryoshka Doll can hold endless versions of herself within her, then perhaps Baba Yaga can do the same, and we need only to twist open her stories to see the secret fragments that make her who she is. Fairy godmothers come in all shapes and sizes, and it may be possible that a gruesome witch can be a blessing to an orphaned child desperate to find her way in a hostile world. You will have to read my story to find out. Kelly Jarvis (she/her) is the Special Projects Writer for Enchanted Conversation: A Fairy Tale Magazine. Her work has appeared in Eternal Haunted Summer, Mermaids Monthly, and Blue Heron Review. When not writing, she teaches classes in writing, literature, and fairy tale at Central Connecticut State University.

0 Comments

Guest Blog by Claire Noelle Thomas This story began with a list of questions. When I was young, I read a lot of fairy tales. They were dazzling, down-to-earth, beautiful, and sometimes frightening, but I loved them all. In most of the stories, the characters’ motivations were clear, whether good or evil. There was no ambiguity about why the villains did awful things. The witch wanted to eat Hansel and Gretel. The evil stepmother envied Snow White’s beauty. The spurned fairy took her revenge on Sleeping Beauty’s parents. Because of this clarity of intention and action, fairy tales always made sense to me on a fundamental level. But not Rumpelstiltskin. For some reason, it left me feeling confused and dissatisfied. I couldn’t put my finger on why the story bothered me, so I began to avoid it. As I got older, I stopped returning to fairy tales as frequently. Something of the magic of that world had been lost to me. The stories didn’t set fire to my imagination like they once did. Then, a few years ago, I found my way back to fairy tales again. This time, I began to glimpse possibilities and gray areas, gaps that I’d never questioned before. All of a sudden, the stories came alive to me, their world richer and more vibrant than ever. I rediscovered Rumpelstiltskin when the Grimms’ tale came up in a fairy tale class I was taking. It still left me feeling hollow and dissatisfied, but this time, instead of shying away from the story, I kept thinking about it. Eventually, I realized that one of the things that bothered me was the lack of clear motivation for the character of Rumpelstiltskin. He appears as a rescuer at first, but quickly becomes a villain. To me, he’s one of the most terrifying fairy tale characters, precisely because his actions are so illogical and inexplicable. Why does he torment the miller’s daughter when he has no connection to her? What’s in it for him? At that point, something clicked for me, and I began to consider all the unanswered questions in this story. Who is Rumpelstiltskin, and what brings him to the castle in the middle of the night? What motivates him to ask the miller’s daughter for her first-born child? Why does he offer her a chance to guess his name when he could simply take the child? And why exhibit such indiscretion in singing his own name aloud? (One could say overconfidence, I suppose, but it’s not a very satisfying answer.) And, perhaps most baffling, why does he tear himself in half at the end of the story? None of these questions had obvious answers, and to me, the story felt like it was more holes than plot. I started toying with the idea that maybe the version we know is only half the tale. What if Rumpelstiltskin actually had perfectly reasonable, even honorable intentions? What was his side of the story? This idea sparked my imagination so much that I decided to try to “redeem” Rumpelstiltskin. Not an easy task when you’re dealing with an extortionist and would-be kidnapper! But as soon as I started writing, everything seemed to fall into place. I glimpsed a pattern I hadn’t seen before, shadows of things already in the tale that just needed to be brought to the forefront. Suddenly, all the elements that had always bothered me about Rumpelstiltskin shifted and turned, revealing a much different face to a story I thought I knew. Giving Rumpelstiltskin a voice and a conscience was painful and challenging. It took me to places within the story that I never noticed before, but it also allowed me to appreciate the original tale in a totally new way. Beneath the apparent cynicism and spitefulness, I found other emotions and motivations at work in these characters. Rumpelstiltskin is a story about greed, yes. But it’s also about possibilities and new beginnings. And, at its heart, it is a celebration of the tenacity of life and hope, even in the harshest conditions.  Guest Blog by Vivica Reeves When the subject of fairy godmother or magical helper comes up, sometimes it is hard to stray away from the image of a kind, old magical being — usually female— who arrives in our darkest hour of need. But what happens in their darkest hour? Who comes to help them? What tragedies encouraged them to help others? These questions spurred on my thoughts and decision to retell the tale of Morozko. Well, actually, I specifically chose Morozko because I wanted a fatherly version of the fairy godmother role. While I could have simply made a fairy godmother in another story a father, I wanted a tale with a godfather in it. I wanted to have him be in and a part of the story, not just a change that I threw in. A main reason for this is because my dad was in the military when I was a kid. My father would leave to go on tours and when he got out of the military, he went onto contract work. Still going, going, and going. While I was not as close to him as I was my mother, I still loved him. He would bring little gifts from his tours or had advice about growing up in the time I did spend with him or see him. I admired him and saw him as the hero of my stories. Better yet, he was like the mystical helper I could rely on, a fairy godfather. Then one day, he couldn’t come to one of my softball games. I was a C-string (low level) player, not that good. But I was promised to be out in the field and playing that game. I told my parents to come. My dad said he couldn’t. He wanted to, but couldn’t. So I shrugged my shoulders. The hero and the magical helper couldn’t be expected to be there at all times. So I went on, thinking he wouldn’t come. But he did. He was there when I played. My team won, and through it all he cheered me on. He told me he wanted to be there because his parents weren’t at any of his games and it wasn’t okay that I was okay with that like he was. In that moment, my dad wasn’t just this magical helper, or hero, but a person. A person who I could connect to and see all the sadness and hurt that I felt too but didn’t know. He knew, he saw my hurt and his own. Together, we healed and he was my dad, my healing helper. At that moment, my dad taught me that everyone has a story. The scars from their story are still hurting. So I read stories and wondered, what happens in this character’s darkest hours? Who comes to help them? What tragedies encouraged them to help (or hurt) others? In my retelling of Morzoko, “Forgetful Frost,” I wanted to show that feeling of connection once more. Yes, Morzoko does help a young girl at her darkest hour. He even saves her from her troubles, but she also helps him. He is also hurting. He is human, despite his magical help. I wanted Forgetful Frost to be a story where people (magical or not) connect and heal together. They became healing helpers to each other. In “Forgetful Frost,” and the other amazing stories in Mothers of Enchantment, we see fairy godmothers (and fathers) at their best and worst. Through these stories, we are asked as readers to see fairy godmothers, or the magical helpers, as people. Not just these magical beings that pop into the story to save the deserving hero or punish the wicked villains. They are not perfect or all-knowing. They can be clumsy, different, wrong, forgetful at the same time they are caring, wise, encouraging, and magical. They are people who are hurting, and healing, and who want to help. So as you read these stories, I encourage you to see where your magical helpers are, and be their healing helpers. Help them and yourself heal. In that healing, lies the true magic. |

World Weaver PressPublishing fantasy, paranormal, and science fiction. Archives

February 2024

|

- Home

-

Books

-

All Books

>

- Beyond the Glass Slipper

- Bite Somebody

- Bite Somebody Else

- Black Pearl Dreaming

- Cassandra Complex

- Causality Loop

- Clockwork, Curses, and Coal

- Continuum

- Corvidae

- Cursed: Wickedly Fun Stories

- Dream Eater

- Equus

- Fae

- Falling of the Moon

- Far Orbit

- Far Orbit Apogee

- Fractured Days

- Frozen Fairy Tales

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Winters

- Grandmother Paradox

- Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline

- Haunted Housewives

- Heir to the Lamp

- He Sees You When He's Creepin': Tales of Krampus

- Into the Moonless Night

- Jack Jetstark's Intergalactic Freakshow

- King of Ash and Bones (ebook)

- Krampusnacht

- Last Dream of Her Mortal Soul

- Meddlers of Moonshine

- Mothers of Enchantment

- Mrs Claus

- Multispecies Cities

- Murder in the Generative Kitchen

- Recognize Fascism

- Scarecrow

- Sirens

- Shards of History

- Shattered Fates

- Skull and Pestle

- Solarpunk (Translation)

- Solarpunk Creatures

- Solomon's Bell

- SonofaWitch!

- Speculative Story Bites

- Trenchcoats, Towers, and Trolls

- Weredog Whisperer

- Wolves and Witches

- Anthologies and Collections

- Novels

- Novellas

- Fairy Tale

- Fantasy

- Romance

- Science Fiction

- Urban/Contemporary Fantasy

- Young Adult SFF

-

All Books

>

- Blog

- About

- Contact

- Press / Publicity

- Newsletter Signup

- Privacy Policy

- Store

RSS Feed

RSS Feed