Guest Blog by Elise Forier Edie I based my fairy godmother tale, "My Last Curse," on an existing story by Baroness D’Aulnoy. In writing it, I tried to solve a mystery that has bothered me for much of my life. Baroness D’Aulnoy was a 17th century writer and fabulist. She is best known for her contes de fees, or fairy tales. One of her most well-known is "The White Doe," which appears in the Orange Fairy Book, edited by Andrew Lang. And that story always struck me as a big, fat mess. I have always been a fan of fairy tales, and Andrew Lang’s twelve colorful volumes hold almost all my favorites. But I’ve also always been puzzled by "The White Doe." The story is filled with powerful and determined females, from a crab fairy, to a Black Princess, to virtuous Desiree, the enchanted White Doe herself. But throughout the tale, all of these wonderful women doom themselves with bad choices. The crab fairy becomes vengeful, the Queen forgets to thank her, the Black Princess never redeems herself, and the White Doe runs off to marry the man who almost kills her. Even as a child, I wondered how poor Desiree could marry the prince who shot her, and why the crab fairy would curse a girl she helped to bring into the world. But once I looked at poor Baroness D’Aulnoy’s life, it all came clear for me. As the editors of Encyclopedia Britannica casually relate, in bloodless prose: “Shortly after her marriage as a young girl in 1666, Marie d’Aulnoy conspired with her mother and their two lovers to accuse falsely Marie’s husband, a middle-aged financier, of high treason. When the plot miscarried, she was forced to spend the next 15 years out of the country.” Um, what? Wow! Here is story of Shakespearean scope and every word of it is true: Act one: Marie is barely sixteen years old when wed to a middle-aged financier. (Ew.) Act two: Marie, her mother—and both their lovers!— form a desperate plan, so young Marie can escape the marriage by having her husband killed (OMG. How much did this guy suck?). Act three: when the plot fails, Marie is thrown in prison. (As a teenager. In the 1600s. Listen, if it was anything like England’s Newgate — the most well-documented prison of the era — it was a hellish place, part underground dungeon and part open sewer). Act four: Marie is pardoned and spends the next thirteen years abroad doing… actually, no one knows. Likely she led an itinerant and desperate existence, scrounging a life for herself by mooching off various friends and acquaintances. But Act Five: she must have made herself charming and indispensable because Marie somehow re-emerges in triumph, as one of Paris society’s most popular authors. And seriously, this fifth act sounds like a wonderful life, one that quite redeemed the horror of the first four. As reported by Jack Zipes in a recent Princeton University Press article: “(Marie) established her own salon on the rue Saint-Benoît, where she often read her fairy tales before they were published. It became customary at d’Aulnoy’s salon to recite fairy tales and on festive occasions to dress up like characters.” (I mean! Cos-play and storytelling! Madame, may I come, too?) Anyway, once I knew the details of this author’s extraordinary life, the conflicts in her strange and convoluted story "The White Doe" made much more sense. Marie’s Princess Desiree is cursed to never see the light of day. She is raised in darkness. Her only escape is marriage, but the engagement transforms her into an animal. She runs away only to be shot and hobbled by her fiancé. What else could a clever, gifted and determined woman of era expect? How else could a girl live as she pleased, in a society crushed by a rigid, unforgiving patriarchy? In tribute to Marie — and to all women who have tried (and still try) to take control of their lives in a vicious and controlling system — I offer "My Last Curse." In this re-telling of "The White Doe" the fairies enchant their girl only to empower her and to give her a chance to fight against unspeakable odds. Their one hope? That Desiree might find a way to thrive and make her own choices. May we all find a way, as Marie d’Aulnoy did, to escape prison, run away and make a life for ourselves on our own terms, and where our own dreams can come true.

0 Comments

Guest Blog by Sonni de Soto I am a broken person. Fact is: you get to a certain age and everyone ends up at least a little damaged. That’s life. Your heart gets broken. The people you depend on disappoint you. Your dreams get lost or delayed. You get hurt and you end up hurting people you never meant to. Life so often grinds away at people, but living and growing is learning how to deal with and heal that damage, so you don’t end up harming yourself or others with those broken bits of yourself. When I saw the submission call for Mothers of Enchantment: New Tales of Fairy Godmothers, I knew I wanted to write a twist on Beauty and the Beast because so little is ever said about the woman who placed that particularly cruel spell. I mean, she took this already bad-tempered, ill-mannered, unlikeable human and cursed him to look like a literal monster. Then she told him the only way he could fix it was to make someone fall in love with him. It’s a harshly impossible task. Why would someone do that? What was she thinking? Fairy godmothers, by archetypal nature, are story guides, characters meant to help heroes grow and learn. So how is this poor, cursed prince — not to mention the story — expected to make her impossible demand possible? Most versions do this by introducing Beauty, this impossibly perfect being. She’s usually not just beautiful on the outside, but so inhumanly filled with patience, compassion, and forgiveness that she somehow transforms this uncouth beast from the inside out. Which is great for the beast, but seems like a lot to ask of a single person. It demands that she constantly sacrifice for and give to and always see the best in this character who really hasn’t done much to deserve it. Her love alone is expected to cure him. Except it’s incredibly unfair to expect our romantic partners to fix us. They are not our therapists or our saviors. They’re regular, normal, broken people who are just looking to find love and be loved in return. Honestly, a story’s hero should learn to fix themselves. They should want to become better, not for the sake of someone else, but for their own. Because, if your happily-ever-after can only be found through someone else… That just sounds like the making of a whole new curse. Because, what happens if that person leaves? Or if they never show up in the first place? In my story “Face in the Mirror,” my beast’s Beauty never shows up, so how — without the help of a miraculously transformative love interest — can my beast ever hope to break the spell? And what will the fairy godmother who cast the curse do when she sees her spell, that was meant to help transform my beastly prince into a better person, go wasted? My story looks at this familiar tale, told countless times, and takes a self-improvement spin on it. It asks what makes a person truly monstrous. How does a person end up acting so much like a beast that they become one? And, if you could take the parts of yourself and your past that feel cursed and change them into qualities that you can love, flaws and all, would that be enough to break the most impossible of spells? Sonni de Soto is a queer author of color, who believes that happily-ever-after comes in many different forms. de Soto has had the privilege of publishing stories with Cleis Press, Speculatively Queer, and many others. To find more from her, please visit patreon.com/sonnidesoto and instagram.com/sonnidesoto_allages.

Guest Blog by Kim Malinowski I created Flick, in “Flick the Fairy Godmother,” because I wanted the protagonist to look and especially feel like I do. In literature, and especially folklore and fantasy, I never see “flawed” characters that are not used as tropes. Characters who have disabilities are rarely, if ever, the main character. These characters are killed off, used as comedic relief, or are somehow “magically cured” at the end. At the very best, these characters become “normal.” Flick is like me. We cannot be “cured” but we can be aided, and our symptoms can be treated. Flick succeeds not just because of her berries and honeysuckle milk, but because she has the inner strength that living with a long-term disability creates. She struggles every second of every day and is shunned by Fae society as “other.” She is awkward and sometimes improper but is always authentic to herself and the world around her. She has doubts and she is not magically cured at the end of the story. In The Wizard of Oz, my personal childhood favorite, The Scarecrow, Tin Man, and The Lion, all find themselves “cured” or at the very least, recognize that they were never flawed to begin with. Flick doesn’t have that realization that she needs a brain or a heart or courage. She does not find them when a “non-flawed” character shows her that she has already has these traits or gives them to her. She does not fight nimbly, but still fights. She decides to believe in her dreams and fully form herself into a nonconventional Fairy Godmother. Flick decides that it is okay to struggle as a Fairy Godmother and that she is flawed and that too is okay. She will leave the battle and still have her internal struggles. She will still have mood swings and panic attacks. She will still have to change her berries when they no longer work. Flick will show the world that it is okay to take medication. It is okay to struggle to get up in the morning, dreading the feelings and the world—but it also shows that she does get up. She can get up. The struggle is hard, and the world can be uncaring. It is necessary for those of us who suffer to get up and do the best that we can. We deal with hard feeling and awkward interactions, but in doing so, we find that we are the heroes in our own stories. Flick is my mirror. She was able to go from completely unable to function to becoming a warrior Fairy Godmother. I might not ever be that type of warrior, but I get up every day. I worry about everything from my dimples to global affairs and either and everything in between can trigger a panic attack. But Flick moves through her daily rituals as do I, and sometimes we go up insurmountable mountains. I tell people that ask for advice, that we must learn to swerve and not just climb straight up the mountain. It might take us longer, but we still reach the peak. Flick shows that it is okay to have a disability. It is okay to struggle. But also, that it is up to us to decide that we are going on the journey.  Guest Blog by Lynden Wade The fairy godmother as a kind and powerful old woman doesn't feature in many of the classic fairytales that are currently canon. Yet she certainly captured the imagination of writers of the nineteenth century, who took the wonder and beauty of the old stories and wove new tales of love and laughter. Here are three examples I love, in ascending order for the role the godmother plays. At the end of the post are details of where you can read them.  The Wonderful Rose, by Netta Syrett The main character in this story is a prince who is discontent with his rather privileged life. His fairy godmother has clearly been spoiling him, as she's brought him many presents over the years, none of which has helped him much, and she half realises this: "Hoity-toity!" exclaimed the old lady; for she had ancient forms of speech. "And so, young man, you are not happy, I hear? What are princes coming to, I should like to know?" Her irritation with the younger generation is fun to read, but she isn't a good deal of use to him. She does give him another gift, that of understanding the language of animals and flowers, and this is crucial later for his growth into a wiser, less selfish young man. But the one whose wisdom sends him on the journey that both helps him grow and leads him to his heart's desire is not the fairy godmother at all but the Wise Woman, who lives in a cave in the heart of the forest. It's tempting to argue that these two women are manifestations of the same goddess, but I doubt if that was Syrett's intention. The fairy godmother, judging from her sniffy response to the prince, where she simply puts into words the prince's father's doubts about the boy, is firmly in the royal court, and it might be that she didn't actually anticipate how life-changing her most recent gift would be. It almost certainly wouldn't have brought him his heart's desire on its own, because he needed to leave all the comfort behind and take a hard journey to win that. Read this tale for the frustrated conversations between the members of the older generation, then love it for its wisdom, as the prince makes an astonishing discovery at the end. The Magic Wishbone, by Charles Dickens Dickens has good fun with fairytale tropes here. The royal family in this story is not rich at all; the king works like a clerk and struggles to make ends meet with his seventeen children. The good fairy Grandmarina wears shot silk and smells of dried lavender. She gives a magic wishbone to the oldest girl, Alice, who holds onto it despite various small family disasters, until it comes to the right moment for making a wish that solves all their problems. Grandmarina appears at the end to remind the king that she was right in entrusting the bone to his daughter, not him. Then she whisks Alice off to a marriage which I hope is simply a ceremony at this point, as earlier clues suggest she is seven, though her prince seems the same age. Read it for the fun way in which the fairy godmother puts the king down. It was especially designed, I'm sure, to delight Victorian children who were constantly told to be good and quiet, but we can all enjoy the adventures of this harassed but ultimately delightful family.  A Toy Princess, by Mary de Morgan In a way, this fairytale is quite grim compared to the ones we've looked at so far, not for nastiness like red-hot shoes or the cutting-off of toes (Snow White and Cinderella in Grimm) but for the forbidding atmosphere in the court in which the young Princess Ursula grows up. But that's the whole point: she's a fish out of water and very unhappy. Luckily, her mother's godmother is on the lookout, and takes her away to grow up with a fisherman and his wife in a plain, loving household. The real fun here is the godmother Taboret's resourcefulness in replacing the princess with an automaton, which she commissions off a magician after haggling with him. Ursula's father and his court much prefer the automaton to the real princess. When Taboret brings the princess back on coming of age, and reveals the deception, the courtiers are quite shocked, and don't like the real princess at all. Taboret's solution is ingenious and Ursula gets the happy ending she needs. Read this beautiful story not just for the very active, intelligent and clever godmother, whose role is equal to the princess's, but also for the way Taboret demonstrates that the automaton is a sham. And then ponder the theme. De Morgan wrote it to show how Victorian manners repressed the spirit. But we can read it in a wider way today, a tale that shows how tempting it can be for us to manipulate people into fitting in with our idea of right behaviour, rather than accepting them for who they are. Where to Read These Stories The Wonderful Rose, by Netta Syrett It was part of the collection "A Garden of Delights", now sadly out of print. However, it is part of the collection "A Book of Princes" selected by Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson, still available to buy online. The Magic Wishbone, by Charles Dickens Read it online here. https://www.storyberries.com/fairy-tales-the-magic-fishbone-by-charles-dickens/ A Toy Princess, by Mary de Morgan Read it online here. https://www.shortstoryproject.com/stories/a-toy-princess/  by Kate Wolford She’s tall and elegant, or tiny with a dowager’s hump. Maybe she’s dressed for a soirée at Versailles or she’s a tired-looking poor old woman who asks nothing more than to have a drink of fresh water from a well. She has many faces, and is often not even a “she,” as men are sometimes cast in this role. This fabled creature is, as you’ve already guessed, the fairy godmother. We remember her best as the generous fairy who dresses Cinderella and handles transportation while she’s at it. But that’s just the most famous fairy godmother’s tale. Baba Yaga is a fairy godmother with a sense of rough justice, rewarding good heroines with what they need to prevail. The fairies in “Diamonds and Toads” and Mother Holle stories are in the vein of Baba Yaga, as they punish unkind young women as equally as they reward their kindly sisters. With just a little more imagination, you’ll find that fairy godmothers/fathers abound in other tales in a less obvious way. I consider Rumpelstiltskin to be a highly misunderstood fairy godfather. He wants a child, and we don’t know that a baby wouldn’t be better off with him or the baby’s actual parents: A terrified mother who was willing to bargain away a future child to save her own life and a greedy father who was willing to kill a hapless miller’s daughter if she couldn’t produce the gold he wanted. Then there’s the fairy in “Beauty and the Beast,” who ultimately creates a beautiful future for the haughty, vain young prince she makes a beast. You could also argue that the little fellows from “The Elves and the Shoemaker” are fairy godfathers, as they create a prosperous future for the very grateful shoemaker, who, in turn, gifts them with clothes. The appeal of the fairy godmother/father lies in our wish that someone might appear, and, with a tap of a jewel-encrusted wand, transform our lives with money, status and great clothes. Better yet, the stories appeal to our sense that someone might notice our own good deeds and reward them, as far too many of us do feel that in this tough old world, no good deed goes unpunished. Yet I think that there is greater appeal in being the magical godparent. What a joy to transform the lives of others with a simple gesture. What a thrill to know you’ve helped make someone’s dreams come true. The good news is, most of us have fairy godparents of a sort, even if they aren’t truly magical, for many people transform our lives with simple generosity and kindness. Perhaps you’ve been in the position to give a neighbor kid the chance to build a lawn care business. Or, you’re the teacher who saw through a sullen student’s mask and suggested books that made her really think for the first time. Or you’re the aunt or uncle who allowed a nephew to stay with you for his senior year of high school so he wouldn’t have to move away from friends. Maybe you’ve befriended a lonely senior citizen who’s now part of your extended family. In any case, the magic of transformation and support is interwoven throughout our lives, and we usually don’t even realize it. Luckily, the authors in this anthology have channeled magic and found gold, and you’ll see that these dozen stories will enchant you and inspire your dreams. In “Wishes to Heaven,” Michelle Tang mixes a fairy godmother in truly unusual form with a pregnant woman who loves her husband and her life with him, but is in dire need of help in the most basic ways. The path Tang takes to manage the story is fascinating and, frankly, unique in my reading experience. In “A Story of Soil and Stardust,” Kelly Jarvis takes us to snowy Russia, and interweaves fairy godmothering, family dynamics and justice, with a special doll and an appealing protagonist to make for a delightful read that sweeps you away. And the dynamics between sisters is riveting in Jarvis’s story. “Real Boy” by Marshall J. Moore is another sweeping story that takes a familiar fairy tale and spins it into a saga of creation, flight, loss and confusion with a satisfying ending. The best thing I can say about this engrossing story is that it was inspired by my least favorite fairy tale. That Moore could overcome my antipathy to the inspiration for his work is testimony to the quality of the story. Lynden Wade takes us into what it’s like to be a fairy godmother in “Returning the Favor.” You’ll fall in love with the fairy godmother in this story, who is wise and loving. And you’ll get a peek into what happens to a fairy godmother’s charge after the “happily ever after.” Most of all, you’ll be startled by the form of the fairy godmother. It all works. Elise Forier Edie brings wit, adventure, humor and exasperation in “My Last Curse.” The ambitions of a too-hopeful and overly controlling Queen make this story great fun to read. And our protagonist is a delightfully sassy fairy in a very unusual form. (Fairy godmothers in unusual forms is a terrific theme in this anthology.) It’s all good fun. Forier Edie’s work has appeared in other anthologies I’ve edited, and you’ll see why when you read “My Last Curse.” “Face in the Mirror” by Sonni de Soto explores “Beauty and the Beast” from a surprising vantage point, with engrossing results. I don’t want to ruin the story for you by saying which other fairy tale it reflects, but I can say that making friendship rather than romantic love the basis for this entertaining and heartwarming story was the best choice. Vivica Reeves weaves loss, love, snow and warmth together artfully in “Forgetful Frost.” The pain of loss and the intensity of true love and parental dedication made this an unforgettable story. Reeves’ words get you in the gut in the best possible way, and the protagonist is an especially touching character. Carter Lappin’s “Modern Magic” is a candy-colored slice of fun involving lattes, smart phones, garbage and bunny slippers. Sounds fun, right? It is fun. You’ll enjoy the modern fairy godmother and her protégée as well as the many charming touches that make this story a light and entertaining read. “In the Name of Gold” by Claire Noelle Thomas, takes us through the deep pain and sacrifice of one of the most beloved fairy tales. The power of ink and quill and true love and friendship make this story shine like gold, and in the end, you’ll feel you know the story Thomas’s work is based on in a new and unforgettable way. Maxine Churchman’s “Of Wishes and Fairies” spins elements like a lost princess and a loving foster mother with the trials and errors of a brand-new fairy godmother to create a sweet and satisfying tale with a happy ending—which is just the ending it should have. You’ll enjoy the fun and lightheartedness of this story. Kim Malinowski’s “Flick: The Fairy Godmother” blends struggles with anxiety with household chores, serious battles and a titular heroine who is always doing her best despite the challenges she faces. You’ll remember Flick, and the brews she ingests to make herself feel better long after you’ve finished reading her story. “The Venetian Glass Girl,” by Abi Marie Palmer rounds out this delightful dozen with a story of exquisite craftsmanship, envy, skullduggery and bigotry into a highly readable and satisfying story that takes you to Venice and its canals as well as a glassblower’s workshop. You’ll be swept away. Before I sign off, there are some people I’d like to thank: Sarena Ulibarri, editor-in-chief of World Weaver Press, who is gracious in the face of the challenges that beset me during every book I edit. Amanda Bergloff, who is essential to my sanity at Enchanted Conversation: A Fairy Tale Magazine, was a great help with editing and formatting the manuscript for this book, and I am most grateful for that. My husband and daughter, and her family, are always great sources of inspiration and love in every creative endeavor I take on, and this book is no exception. My grandson Ben gives me a great incentive to put together books that he will someday enjoy. I thank them all. Finally, the readers and writers at Enchanted Conversation make me want to do my best because their love of fairy tales and folklore rivals my own, and they have my gratitude. May this book bring you as much joy as a tap of the wand from your fairy godmother. Kate Wolford is a writer, editor, and blogger living in the Midwest. Fairy tales are her specialty. Previous books include Beyond the Glass Slipper: Ten Neglected Fairy Tales to Fall in Love With, Krampusnacht: Twelve Nights of Krampus, Frozen Fairy Tales, and Skull and Pestle: New Tales of Baba Yaga all published by World Weaver Press. She was the founder of Enchanted Conversation: A Fairy Tale Magazine, at fairytalemagazine.com.

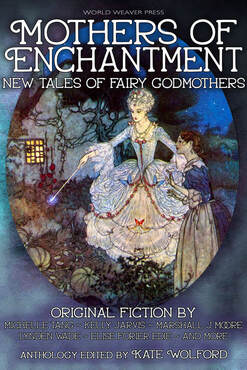

Your wish has been granted! Mothers of Enchantment: New Tales of Fairy Godmothers is out in ebook and paperback today, April 19, 2022. These stories flip traditional fairy tales on their heads to show the story from the point of view of the fairy godmother herself. (Or, the fairy godfather himself.) Some are set in the modern day, like "Modern Magic" by Carter Lappin which features a Starbucks-drinking Basic Godmother helping a young woman impress at her high school reunion; some are set in a historical period, like "The Venetian Glass Girl" by Abi Marie Palmer which takes us to the moon-drenched canals of nineteenth-century Venice. Still others mix a way-back setting with a modern sensibility, like "My Last Curse" by Elise Forier Edie, in which the fairy godmothers play a centuries-long game to fight the fairy godfathers. Click here to listen to some of the authors read an excerpt from their stories, and look below to find a link to your favorite online bookseller. You can always request a copy through your local independent bookstore, or request that your library order a copy! “…it’s a charming concept, and Wolford’s love for fairy godmother tropes shines. Fans of contemporary fairy tales will find this worth a look.” “If you’re interested in fantasy or mythology, this collection is well worth a read. It provides ample evidence that fairy godmothers are people too.” |

World Weaver PressPublishing fantasy, paranormal, and science fiction. Archives

February 2024

|

- Home

-

Books

-

All Books

>

- Beyond the Glass Slipper

- Bite Somebody

- Bite Somebody Else

- Black Pearl Dreaming

- Cassandra Complex

- Causality Loop

- Clockwork, Curses, and Coal

- Continuum

- Corvidae

- Cursed: Wickedly Fun Stories

- Dream Eater

- Equus

- Fae

- Falling of the Moon

- Far Orbit

- Far Orbit Apogee

- Fractured Days

- Frozen Fairy Tales

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Winters

- Grandmother Paradox

- Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline

- Haunted Housewives

- Heir to the Lamp

- He Sees You When He's Creepin': Tales of Krampus

- Into the Moonless Night

- Jack Jetstark's Intergalactic Freakshow

- King of Ash and Bones (ebook)

- Krampusnacht

- Last Dream of Her Mortal Soul

- Meddlers of Moonshine

- Mothers of Enchantment

- Mrs Claus

- Multispecies Cities

- Murder in the Generative Kitchen

- Recognize Fascism

- Scarecrow

- Sirens

- Shards of History

- Shattered Fates

- Skull and Pestle

- Solarpunk (Translation)

- Solarpunk Creatures

- Solomon's Bell

- SonofaWitch!

- Speculative Story Bites

- Trenchcoats, Towers, and Trolls

- Weredog Whisperer

- Wolves and Witches

- Anthologies and Collections

- Novels

- Novellas

- Fairy Tale

- Fantasy

- Romance

- Science Fiction

- Urban/Contemporary Fantasy

- Young Adult SFF

-

All Books

>

- Blog

- About

- Contact

- Press / Publicity

- Newsletter Signup

- Privacy Policy

- Store

RSS Feed

RSS Feed