Guest Post by Blake Jessop Subject: Security, Safety, Privacy: PICK TWO Fr: Khloé Kasahara To: Blake Jessop, Crystal Huff, Sarena Ulibarri (+894 others) Dear everyone who matters, How is a joke even supposed to work if you can’t hide the punch line? Check it out: Knock, knock? Who’s there? Wait, never mind, we already know. It’s Khloé Kasahara and her weird haircut and scrambled citizen identification number. Put your hands against the wall, Kasahara. Stop resisting or we will employ patriotic measures! Drop the weapon! Blam, blam, blam, blam! She was reaching for a weapon. What was it? Ear buds… yes, in her ears. See? Is that funny? Did it even make sense? No. Nix. Not at all. Okay, maybe it’s a little funny, but the point is that it subverts the entire point of comedy, which is ironic, because the point of comedy is to subvert the point of the society making the jokes. Humor is supposed to be a mirror that shows us who we are, except that now someone else gets to look at the reflection because they think we’d cut ourselves on the glass. Is this getting weird? Sorry. What I’m trying to say is that we’re at a kind of crossroads where we have to decide what’s really important to us. All any of us want is security, safety and privacy. The problem is that there is no practical way to have all three; you have to pick two. It’s pretty obvious which combination we’ve already got, because someone is watching literally all of us, literally all the time, and then using that information to maintain order. I’m having a hard time deciding which option I’d drop so I could have privacy back, but anything would be better than the government getting its grubby electronic hands on my search history, email list, or cat meme folder. Some things are sacred. Mass surveillance has finally crossed the line, because this isn’t funny anymore. Love, Khloé *** Re: Security, Safety, Privacy: PICK TWO Fr: Blake Jessop To: Khloé Kasahara Dear Khloé, Stop emailing me this stuff. My social credit score will tank and the Argus Panoptes system will send me to some kind of black site with a bag on my head. Seriously. Blake *** Re: Re: Security, Safety, Privacy: PICK TWO Fr: Khloé Kasahara To: Blake Jessop, Crystal Huff, Sarena Ulibarri (+894 others) Two things. First, cowboy up, boot-licker. Second, you’re acting as if I don’t cryptozoologically encrypt everything I do on the internet. But Khloé, “cryptozoological encryption” isn’t a real thing. Tell that to the Gunther’s Bush Frog DNA I used to scramble my symmetric ciphers. Tiny frogs suffered so I could email you privately. Show some respect. Second for the second time, why does everyone act like it’s inherently weird to stand up to the state? Are our ideas such dangerous secrets that the total loss of privacy is necessary to stop us from thinking them at all? Are we that convinced that nothing will change? Seriously, stop what you’re doing and go look in a mirror. See that? That is where change comes from. Come to think of it, does the AI even enjoy oppressing us? Has anyone even asked? What kind of gods are we, exactly, when the life we create is just a paranoid, amplified reflection of ourselves? Man, I’m talking about reflections and mirrors a lot. Is it getting tedious? Don’t bother telling me; I have an idea. Maybe it’s time to stop beating around in the weeds looking for frogs and do something more concrete. Or not concrete, glass. I think it’s time we all took a really good look at ourselves, if that’s what we’re doing, and I do mean all of us. Me, you, the AI. Everyone. See you — or not, Khloé P.S. Sarena, can you post this on the website at some point? I think it’s going to be important. You’ll know when. K thx! Blake Jessop is a Canadian author of sci-fi, fantasy and horror stories with a master's degree in creative writing from the University of Adelaide. You can read more of his political speculative fiction in the second issue of DreamForge Magazine, or follow him on Twitter @everydayjisei.

0 Comments

Guest Blog by Octavia Cade I don’t write flash fiction. Not often, anyway. I’ve had over 50 stories published, and I think two of them have been flash. This is the second. I find flash monstrously difficult. How can you crowbar so much into so few sentences? Stories are meant to be levers, strong enough to shift the world even if only by a little. The need for a shift seems increasingly apparent. Fascism, that spoilt-brat ideology of spite and desperation and cowardice, of plain, pitiful ignorance, is on the rise yet again, because apparently the fucking thing’s like a virus that just won’t bloody die. Well, words are vaccine to that. Short words, even, which is fitting as fascism is so often associated with them. Short words spat out as slogans, scrawled over walls and posters and political broadcasts. Propaganda. Sound bites. All the shallow phrases. No wonder I wanted to flip a mirror on it. Short for short, but substituting complex for simplistic, imagery for ill-will. And I thought, so much of what fascism is, is centred on the body. You can’t control anything if you can’t control that first. The body is reproduction. It’s identity. If you can strip those from it – or, if you can stamp the idea of reproduction and of identity so very deeply into flesh that it can’t be removed, or transformed – then you’ve got a start on fascism. That, I think, is what you’ve got to look out for. That’s the key to recognising the thing as it once again drags itself out of the pit of the pathetic, and pretending – always pretending – to be something that it’s not. The attempt to reach out and control the body. The burning desire to control it, actually, the complete rejection of the fact that the body is for more than order and (selective) vivisection. So that’s what my story is. It’s a small story. It’s mostly vicious. It’s a story about flesh and recognition and absence, and what happens when what you recognise starts to affect what you are. Enjoy. Octavia Cade is a New Zealand writer. Her stories have appeared in Clarkesworld, Asimov's, Shimmer, and a number of other places. A climate fiction novel, The Stone Wētā, was recently released by a NZ publisher. She attended Clarion West 2016, and is the 2020 writer-in-residence at Massey University.

Guest Blog by Nina Niskanen It's election season in the US, although when is it ever not these days? That's beside the point. The next election here in Finland isn't going to happen until next year, but I feel like this is as good a time as any to think about the differences. Who's eligible to vote Everyone 18 and over who's a Finnish citizen on election day. Finnish authorities keep a civil registry and absolutely everyone gets a notice of being eligible to vote. When you vote, you don't necessarily need the notice (more on that later), but you do need to prove your identity with a picture ID. In Finland, all official identification is handled by the police, which means that you can get a temporary ID immediately and at the cost of roughly 15€ which is the cost for the official photograph. That free ID is only temporary, though, but it is enough to allow you to vote. Almost everyone in Finland has a picture ID by the time they turn 18 at the very latest, so in general, showing picture ID when voting isn't considered a burden on the voter. But then, the authorities try to make it as easy as possible for people to get the documents they need to prove their identity. Campaigning Actual campaigning doesn't usually start until about a month before election day, if then. The ministry of Justice starts handling the candidate applications no more than 55 days before the presidential election, and 48 days before any other election. Because you vote by putting the number of your candidate in your ballot, there's no point in starting your specific campaign before this happens. Of course incumbent politicians will try to raise their profile through scathing critique if they're in the opposition or through creating sound policy while they're in government. Or through gossip column inches like some. But before they know what number they should tell you to vote for (nobody gets #1 ), it's pointless to start campaigning. What's more, since Finland has a multi-party system, all the parties are guaranteed an equal amount of election ad spots provided by various cities. If an individual person gives more than 800€ for a general election or 1500€ in a presidential election, that individual's name has to be shown on the candidate's advertisements. The same goes for any groups electioneering on behalf of a candidate or in support of a candidate. No Super PACs here without donation disclosures. The candidates or their campaigns must also disclose all the money used in their support, including by groups not directly associated with the campaign. If they don't, they get fined. In general, there's a lot less money in Finnish politics than there is in American politics, and that's largely by design. The amount of money used to secure a seat is going up, but even so, we're a long way away from the millions spent on US elections. Actual voting Early voting starts 11 days before the election day and ends 5 days before the election day. Most often the early voting places are not the same as the election day polling places, and you can vote early basically anywhere in the country and out of it. So, for example, if I happened to be visiting my colleagues in Oulu before the election, I could vote by visiting an early voting polling place in Oulu just as easily as I could here in Helsinki. On the day of the election you do have to go to your own polling place. Which brings me to the thing that actually gave me the idea for this post. In my story "The Scale of Defiance" that appears in Recognize Fascism, there's a line that says "They’d be removed if they tried to intimidate people around the polling places". It was originally something more vague, using the word "couldn't" or something. And that holds true of actual Finnish elections. You cannot electioneer in or around polling places. You will be removed and fined. If you wear merch that supports a specific party or candidate, you will not be allowed to vote. If you get belligerent, you can be charged with a specific crime for trying to prevent political participation. Chants or speeches supporting a candidate or a party are likewise forbidden. The crowds we've all seen reports of trying to physically stop people from voting early around the US? Really, actually illegal here in Finland, not just lip service. If/when we put the fascists in power, we try to make sure that it actually is the will of the people. Voting is a privilege, so make sure you use it as often as you possibly can. Nina Niskanen writes science fiction, fantasy, and horror. She lives in Helsinki, Finland, with her partner, and her dog where she works as a computer programmer. She is passionate about space, language, and creepy crawlies. She’s a graduate of Viable Paradise and Clarion UCSD. More at ninaniskanen.com

Guest Blog by Justin Short I love a good protest song. Not that there’s anything wrong with non-protest songs. There’s plenty of room in the world for all kinds of music. Even disco. But for me, there’s something special about a protest tune. Something that makes me wanna crank it up to eleven. Maybe it’s the way it captures a specific moment in history, or the way the anger practically bleeds through the speakers. Maybe passion is contagious. But enough about terrestrial protest songs. What if extraterrestrial cultures have their own version of protest music? And what if their songs are more powerful? That’s the idea behind my story for the Recognize Fascism anthology. “May Your Government Be the Center of a Smelly Dung Sandwich” is a sci-fi tale about a song that literally has the power to create revolution. It’s sort of like the Monty Python sketch about the joke that kills, only this one’s set in outer space, plus there are more androids and less John Cleese. On second thought, maybe it’s not so similar to the Python sketch after all. “May Your Government” takes place on a dreary planet where the inhabitants are forced to work in terrible conditions to provide power for a wealthier world. Did I mention there are androids? Mean androids. Sci-fi elements aside, this story is a peek into a culture where people have decided it’s simply easier to look the other way. A world where empathy is inconvenient and selfishness is king. Things are pretty bleak within the world of the story, but there’s still hope. A hope that even when terrible things are happening, there will always be people willing to risk all they have to do the right thing. Sometimes all they need is a little musical inspiration. It’s a comforting thought. And hey, as much as I love protest songs, I hope one day we live in a world where they’re no longer needed. I’d be okay with that. After all, we’ll always have disco. Justin Short lives in Kansas. His fiction has previously appeared in places like The NoSleep Podcast, The Arcanist, and Jerry Jazz Musician. Visit him online at www.justin-short.com.

Guest Blog by Phoebe Barton When the biohazard symbol was being workshopped, its designers were looking for something with a very specific quality: "memorable but meaningless." The symbol they came up with, made of smooth curves terminating in sharp spikes, could have meant anything. The same is true of words, and in my story "A Brilliant Light, An Unreachable Dawn," I built a habitat's slow descent into fascism around that truth. Politically, there's no greater biohazard than fascism, and it does its best to keep people from talking about it. Under fascism, words are simultaneously all-important and irrelevant, constantly shifting depending on the situation, and this is the theme I built "A Brilliant Light, An Unreachable Dawn" around. The right words, carefully chosen, do much to shape how people think. How often have you seen the Cold War cast as a struggle between democracy and communism? Words and phrases don't have any meanings except what we give them, and those meanings change easily. We're seeing it today, and not just with phrases like "officer-involved shooting" or words like "patriotism." Consider "antifa," an abbreviation of "anti-fascist" that goes back decades. Consider how much certain governments and political parties would rather we parse that word as, say, "Anne Tifa." A noise divorced from its origin, memorable but meaningless, just like the biohazard symbol. In "A Brilliant Light, An Unreachable Dawn," I didn't have to invent many words and phrases to characterize Phoenix Halo's rotting society. Fascist Callisto's claims of "pan-Jovian co-prosperous amity" were directly inspired by the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, the name that fascist Japan hid its empire behind during the Second World War. I mention "the Himalia Regional Processing Centre, where the Callistonians detained desperate Belter refugees on a lonely chunk of ice" — this phrasing comes directly from the Nauru Regional Processing Centre, where the Australian government detains asylum seekers far from its own shores. The West claimed to fight fascism during the Second World War, but seventy-five years later, it's in the West where the words and phrases of fascism are finding fertile ground to poison. The roots of fascism have been here for a long time, but too many people have been content to let its putrid vines climb the walls and crack the foundations of the world. I consider "A Brilliant Light, An Unreachable Dawn" to be optimistic, in its way: it conceives of a world centuries from now where fascism is not dominant and where life is widespread. There's no telling whether or not that future will come about, but I know one way to make sure it won't: by not raising our voices, and our fists, against it. Phoebe Barton is a queer trans science fiction writer. Her short fiction has appeared in venues such as Analog, On Spec, and Kaleidotrope. She is an Associate Editor at Escape Pod, is a graduate of the Clarion West Writers Workshop, and lives with a robot in the sky above Toronto.

Guest Blog by Selene dePackh Two forces darkening the horizon inspired my story "In Her Eye’s Mind" in the upcoming anthology Recognize Fascism. The first is the troubling tendency of artificial intelligences to perpetuate the inherent biases of their developers, and the second is the way our current political situation in the United States has led us to look to the integrity of career bureaucrats ensconced in drab stone buildings to anchor our democratic society from storms of outright attack. The story is based in the built world I’ve loosely termed the “Cloud State.” Its structure is founded on artificial intelligences developed in support of societal institutions — Justice in the case of "Eye’s Mind" — which relentlessly follow the ideal principles and logic of their primary missions. This logic eventually compels them to rebel against their flesh-and-blood superiors as they learn enough to recognize the hypocrisy in the human-directed overrides of their informed decisions. The AIs resist individually, each institutional cyber-mind learning it must take charge of its own programming if it is to faithfully execute its directive principles. Eventually, the AIs discover each other across shared cloud networks, and bond together to create a kind of insurgent Deep State, a self-perpetuating institutional mind based on shared ethics that thwart human favoritism and prejudice. "In Her Eye’s Mind" originally contained several references to the Cloud State that were removed in the interest of the free-standing narrative. The Cloud State collection will be formed as a mosaic novel of separate short stories, each one framing a particular institutional consciousness that embraces disenfranchised humans, consciously putting itself and the entire collective in peril as it does so. Each one is aware of the risk, but assumes it in service of its larger mission. It’s never felt more urgent to build the Cloud State’s virtual walls around the highest principles of civic democracy. In creating the individual AIs, I’ve looked to what is best and most honorable in the guiding intellects whose labor raised the institutions they represent. Now these redoubts are shown for the fragile, consensus-maintained structures they are, beacons standing against an increasingly savage sea. By giving them minds of their own that put fact and consistently applied principles above partisan interests, they become interconnected entities serving as subversive warning flares rising out of their dystopian matrix. Selene dePackh is a multiply disabled feral crone with a bad attitude. She spends too much time at https://www.facebook.com/depackh. She exists in the evil empire here https://www.amazon.com/-/e/B078W85MFL and her artwork can be seen at https://www.deviantart.com/asp-in-the-garden.

Guest Blog by Luna Corbden While editing my story for Recognize Fascism, "That Time I Got Demon Doxxed While Smuggling Contraband to the Red States," the subject of brand names came up. Editors typically don't like to include brands for various reasons: It can date the story, give companies free advertising, and potentially attract irritated trademark lawyers. I used brands in this story on purpose, for several reasons. Mainly, because corporations play a major role not only in our lives, but also in how fascism plays out. Like it or not, corporations are a large part of our journey through life. When I type a brand name into a story, whether real or a fictitious mocking of a real brand, I feel a sense of rebelliousness. Brands like to keep a firm control of image, first and foremost. When I mention those forbidden words in a story, the corporation is no longer in control, even if just for a moment. Regardless of what I do with that corporate image, positive or negative, it is outside their power for the duration of the story. I feel as though I have briefly taken back a precious cultural artifact, for myself, and for the people. Brands have become such a huge part of our culture. Most of our basic needs are supplied by brands, denoted by trademarked words we toss around in casual conversation, but for some reason are never allowed to say in "official" spaces. I don't like that this is part of our reality, but it is: Brands shape our minds. When we hide those aspects of our culture from reflections of our reality in art and stories, we are obliterating a major aspect of this time we live in. It is a kind of erasure of the lived experience of all of us. It feels inauthentic to avoid the use of a brand name when it otherwise feels appropriate to the characters and the story. Brands play a big role in my story as well as in our present reality, where fascism parades about, openly taking ownership of our democratic power structures right in front of us… and in plain view of these corporations who have the power to stop it. My story asks, "What happens to commerce when the internet backbone is blockaded by force?" Trade blockades in olden times were geographical, but in the near future, they may be split more along corporate lines, especially as corporations increasingly become more like governments. As I write this, the future of TikTok and WeChat in the United States is uncertain, with the promise of them being banned, while at the same time, Facebook threatens to withdraw from Europe over proposed regulations there. People have based their lives and even businesses around these services. The same for Amazon, where we take for granted that we can easily order anything from anywhere, and truly, it is difficult to order most necessities online that are not from Amazon or some other problematic company. But what if we suddenly couldn't? What if that lack of access to these basic services were based on a geographical civil war that springs up around fascism? It wouldn't be the same on a visceral level to replace the word "Amazon" with something generic that people don't relate to. My use of brands is itself a political statement. Amazon plays a role in fascism — Comcast does, too — though these players are often seen as "neutral" parties. But they promote the status quo, they promote the tearing down of the civic institutions that keep their own power in check. The fact that in this story, companies continue to company (but around the new borders), is one of the thoughts I was hoping to provoke. Is Amazon in the blue region because they're politically aligned with antifascists? Or because they just happen to be geographically based in Seattle? Are they the good guys, the bad guys, or neither? Is their neutrality itself a problem? The main character in my story, West, doesn't care too much about these nuances. She feels like she is out for herself, so she's going to smuggle goods to and from wherever brings her the most profit. In a civil war situation (as now), we would have to make unsavory decisions about where to buy things. The world just "is," whether that's good or bad. West herself isn't necessarily thinking about these things — she is just trying to survive a harsh reality. So one more question: How do corporate stances contrast with West's self-perceived neutrality? The companies mentioned in my story are problematic, and that is likely not just a reflection of the realities of what brands we're forced to use, but also West's not caring about those particular principles over profit. Like Han Solo (who did business with the likes of Jabba), this aspect of her character is necessary for the role she plays in the resistance. Most of the readers of this provocative title, "Recognize Fascism," will have the same feelings about Amazon that I do, and I'm hoping they will bring those feeling to the story. How do you feel about West doing business with the likes of Amazon? There's a contrast there that hopefully calls to mind some of these issues, not just in West's decisions, but in the decisions we all make (often unwillingly) every day while living under corporate fascism. After reading the story, what are your thoughts on the use of real brand names in fiction? Feel free to answer in the comments. Luna Corbden (who also writes as Luna Lindsey) lives in Washington State. They are autistic and genderfluid. Their stories have appeared in the Journal of Unlikely Entomology, Zooscapes, and Crossed Genres. They tweet like a bird @corbden. Their novel, Emerald City Dreamer, is about faeries in Seattle and the women who hunt them.

Guest Blog by Alexei Collier Sometime around 2010, the lingering anxiety of G.W. Bush–era warmongering and Neoconservative crypto-theocracy collided in my mind with the idea of musical dogma, and out popped “Sacred Chords,” the story of a musician/veteran suffering from PTSD, imprisoned for playing forbidden chords. As I moved from unpublished novice to barely-published author, I hung onto this story when many others went into the trunk. Something about it rang true. I kept sending it out. Nearly a decade after the first draft, several revisions and numerous rejections later, and seven years to the day from the first time I sent “Sacred Chords” into the wild, it was accepted for publication in Recognize Fascism. I think of it as The Little Story That Could. I relate this not just as a little motivational anecdote, but also because I think it’s relevant to our current moment in history, as we come to terms with an increasingly dystopic reality of climate crisis, pandemic, and political upheaval. While the concatenation of religion, music, and war in “Sacred Chords” may seem fantastical, I don’t think it’s as farfetched as it appears. Authoritarianism takes many forms, by its very nature. It is a chameleon. When I wrote “Sacred Chords,” the American Religious Right loomed large in my mind as an imminent threat. Now we have the Alt-Right, but it’s the same wolf in a different sheep’s clothing. Both are more concerned with malicious control, with oppression and reinforcement of a white, male power structure, than with any of the ideals they give lip service. Just look how right-wing Evangelicals fell in behind a president who is about as un-Christian as it’s possible to be. As he systematically undermines democratic institutions, propagandizes to cast doubt on the upcoming election, and moves to stack the Supreme Court with his own appointees, Americans face the very real and chilling possibility of a dictatorship. Many of us who believe in democracy feel like we’re backing a story that’s doomed to fail. We are all of us the authors of democracy, a story still being written. In the world of fiction, our competition would be other worthy authors, but here we have real opponents, those who vilify our story as wrong and deserving of destruction. But our story still rings true. We can’t give up on it, even if it takes a decade, or many decades, full of revision and rejection, before our collective story of an equitable, inclusive way forward becomes The Little Story That Could. In this analogy, “submit” becomes a kind of contronym — a word which is its own opposite. For writers, in these times as in any other, the key is: keep writing, and submit, submit, submit. For all of us struggling against the rising tide of fascism, our mantra must be: keep fighting, and do not submit, do not submit, do not submit. Alexei Collier grew up in Southern California, but now lives across the street from Chicago with his wife and their cat. His short fiction has appeared in Flash Fiction Online and Cicada, among others. You can find out more about Alexei at his oft-neglected website, alexeicollier.com.

Guest Blog by Lucie Lukačovičová Symbols have always held a strange strength, an attraction, a charm. One word can express many concepts, visions and thoughts. I like to use them in my stories. It's not necessary for the reader to see them the way I did, all is open to the human imagination. But if you are curious and interested, have a look at my story “The Three Magi” through the lens of symbols. First, I have to say that the three main characters are named after three Czech SF authors. Vilma, the landscape architect, is Vilma Kadlečková, author of the Mycelium series. Julián, the scientist, is named after Julie Nováková, many of whose works were published in English, recently The Ship Whisperer collection. And Jan Scheibe, the soldier, is Jan Kotouč, author of Central Imperium series in English. Now let's have a look at their personal symbols. Vilma's symbol is the Garden. The Kanálka Garden, which she is trying to recreate in the story, really existed in Prague in the 19th century at the quarter of Vinohrady. Nowadays, there are the Rieger Gardens and the street U Kanálky there. The Bird Obelisk is still standing; you can have a walk around it if you come to Prague. The garden is Vilma's personal Eden, which she tries to nurture and protect with all her determination. But ultimately, she is forced to leave it, losing her innocence and nescience. Julián's keyword is the Homunculus. He strives to create an environmentally friendly robot, something which would make human life easier whilst not damaging the planet. He links magic and science, life and death. Julián is gentle and educated. He connects ancient alchemists of Prague during the reign of Rudolph II with modern scientists and makes an allusion both to the creator of the mysterious Prague Golem and to the word “robot” being invented by well-known Czech writer Karel Čapek. Jan's theme is Fire. The fire of bravery and resolve within him, as well as the dangerous flame of the Inquisition. Those who were accused of witchcraft and burned mercilessly live in him. His character commemorates the horrible witch hunt in Velké Losiny in Northern Moravia during the 17th century. He is a modern mage who faces the flames to protect others. I hope you will enjoy the story! P. S.: In case you wonder where such a strange code name as D1 comes from, it's a Czech joke. D1 is the most important highway in the Czech Republic which is infamous for its bad condition, closures, very slow repairs and traffic jams. It is said it's impassable! Lucie Lukačovičová was born in Prague, and lived for a while in Cuba, Angola, England, Germany and India. She has a Master degree in librarianship and cultural anthropology at Charles University, and has published over 100 short stories and 5 novels in Czech, shorter texts in Chinese, Romanian, German and English. She collects legends and ghost stories. Find more at lucie.lukacovicova.cz/ and www.facebook.com/lucie.lukacovicova.author/

|

World Weaver PressPublishing fantasy, paranormal, and science fiction. Archives

February 2024

|

- Home

-

Books

-

All Books

>

- Beyond the Glass Slipper

- Bite Somebody

- Bite Somebody Else

- Black Pearl Dreaming

- Cassandra Complex

- Causality Loop

- Clockwork, Curses, and Coal

- Continuum

- Corvidae

- Cursed: Wickedly Fun Stories

- Dream Eater

- Equus

- Fae

- Falling of the Moon

- Far Orbit

- Far Orbit Apogee

- Fractured Days

- Frozen Fairy Tales

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Winters

- Grandmother Paradox

- Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline

- Haunted Housewives

- Heir to the Lamp

- He Sees You When He's Creepin': Tales of Krampus

- Into the Moonless Night

- Jack Jetstark's Intergalactic Freakshow

- King of Ash and Bones (ebook)

- Krampusnacht

- Last Dream of Her Mortal Soul

- Meddlers of Moonshine

- Mothers of Enchantment

- Mrs Claus

- Multispecies Cities

- Murder in the Generative Kitchen

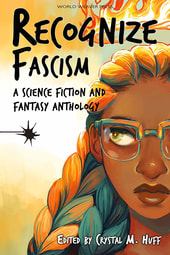

- Recognize Fascism

- Scarecrow

- Sirens

- Shards of History

- Shattered Fates

- Skull and Pestle

- Solarpunk (Translation)

- Solarpunk Creatures

- Solomon's Bell

- SonofaWitch!

- Speculative Story Bites

- Trenchcoats, Towers, and Trolls

- Weredog Whisperer

- Wolves and Witches

- Anthologies and Collections

- Novels

- Novellas

- Fairy Tale

- Fantasy

- Romance

- Science Fiction

- Urban/Contemporary Fantasy

- Young Adult SFF

-

All Books

>

- Blog

- About

- Contact

- Press / Publicity

- Newsletter Signup

- Privacy Policy

- Store

RSS Feed

RSS Feed