|

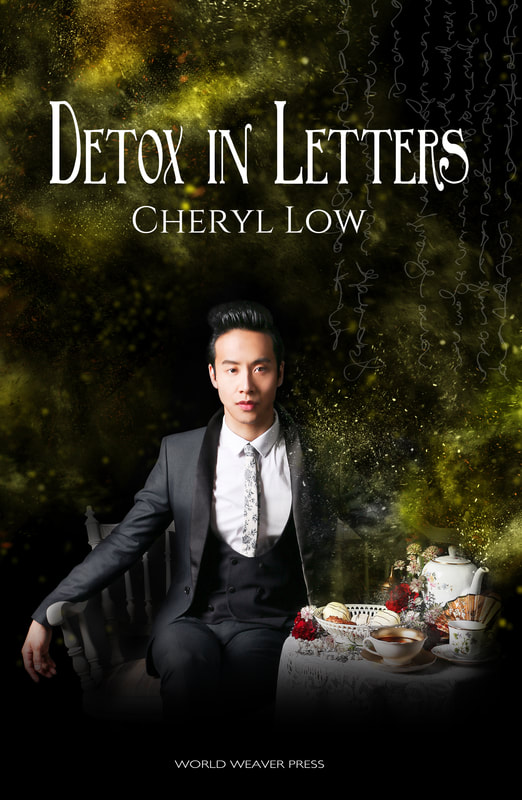

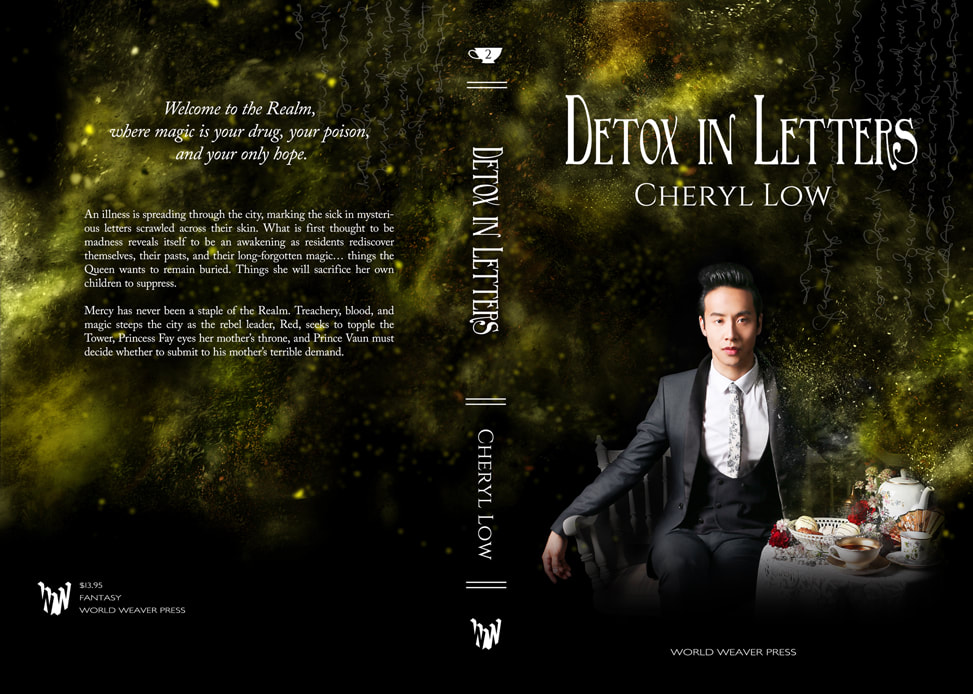

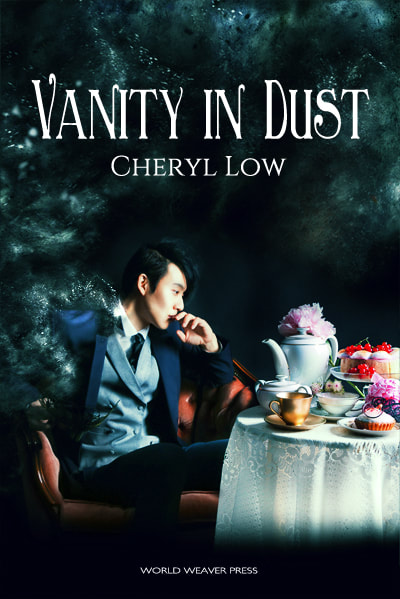

We have a treat for you today: the delicious cover for Detox in Letters, the second book in Cheryl Low’s Crowns & Ash series, which will be available in trade paperback and ebook on Tuesday, September 18, 2018. Set in a decadent fantasy world of power and passion, Detox in Letters is about a strange madness that grips the residents of an isolated realm as they begin to remember what the world was like before the oppressive rule of the queen who keeps them all drugged with magical dust. Detox in Letters follows Low’s 2017 debut, Vanity in Dust. Welcome to the Realm, where magic is your drug, your poison, and your only hope. Need to Catch up on the First Book?

In the Realm there are whispers. Whispers that the city used to be a different place. That before the Queen ruled there was a sky beyond the clouds and a world beyond their streets. About the Author  Cheryl Low might be a dragon with a habit of destroying heroes, lounging in piles of shiny treasure, and abducting royals—a job she fell into after a short, failed attempt at being a mermaid. She can’t swim and eventually the other mermaids figured it out. She can, though, breathe fire and crush bones, so being a dragon suited her just fine. …Or she might be a woman with a very active imagination, no desire to be outdoors, and more notebooks than she’ll ever know what to do with. Find out by following her on social media @cherylwlow or check her webpage, CherylLow.com. The answer might surprise you! But it probably won’t.

0 Comments

It's time to celebrate our bestsellers for the first half of 2018! We're happy to see that it's a solid mix of newer releases (such as The Continuum, Mrs. Claus, and Dream Eater) as well as some of our fan favorite backlist (such as Fae, Krampusnacht, and Beyond the Glass Slipper). Want to see how it stacks up to last year? See the June 2017 bestseller list here, and the December 2017 bestseller list here. Below, you'll find our top 10 bestsellers for the first half of 2018, as well as a list of our top 10 bestsellers of all time. Is your favorite on these lists? Let us know in the comments! A few notes on these rankings:

Sarena Ulibarri Editor-in-Chief Top 10 bestsellers: 1st Half 2018

Top 10 All-Time Bestsellers, 2012-present

by Helen Kenwright I first read E.F. Schumacher's Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered back in the late 1980s. I'd just finished my BA in Sociology, and was working for a Fair Trade shop in York. It was one of a collection of books that gave me hope amid the spectre of crumbling capitalism, environmental destruction and triumphant patriarchy we were headed for. The Green movement offered an alternate vision of society to fight for: one based on community, social justice and ecology. I've been a hopeful Green ever since, and with every campaign I’m involved in, every election I fight, every piece of policy I help to develop, I become more convinced that three things will save us from the dystopia so many consider us doomed to face. The first is that human beings show immense capacity for change and adaptation. The second is that while the climate deniers have been denying, and capitalism has been issuing vague, unrealistic promises, scientists have been developing amazing technology that could just save us. The third (and most important) is that we still have hope. All we need is the will, and that, I believe, comes from the imagination. That’s where us writers and artists come in. In solarpunk I found an artistic movement to match the political ideals I've worked for all these years, and the idea of White Water swiftly followed. Berta’s world would have the world-saving sustainable technologies we expect of solarpunk. She lives in a future where we woke up in time and saved our world from destruction. But just as important, for me, is to explore what communities are like in a sustainable future. Schumacher's 'small is beautiful' philosophy predicted not only the economic disasters of global economies, but also the cost to human wellbeing. He foretold the rise of mental illness we are now experiencing. He argued that small communities with a focus on meeting local needs led to more healthy human relationships. The community is recognised as an ecosystem, where diversity is a source of strength and we benefit from the development of individual skills and interests. So White Water is one vision of what a solarpunk, Schumacher-inspired world might look like: independent, inter-related communities, growing most of their own food, generating their own power, building their own lives. The more solarpunk I write, the more fascinating questions spring to mind. If technology is used to give us all more time (rather than some of us more money), what would people do with that time? If we truly accept our place as part of our natural environment, rather than trying to subdue or own it, how does that affect the way we treat our world? If we celebrate rather than fear diversity, how would that impact our interactions, our governance, our relationships? What would change? And what would stay the same? Berta has special gifts, which represent the magic that patriarchy stifles in our current world. Who knows what human talents might emerge, if we are free to explore them? There's so many more aspects of this world I want to explore through the community of White Water. I want to know what life's like for Reg, a transgender person in a society where gender fluidity is accepted as a part of life. How do people cope with the inevitable scarcity of a sustainable world? Many of these questions also appear in other brilliant works in the 'Glass and Garden’ anthology. Solarpunk is not utopia, and it is not a single vision: it is a host of fairer, more sustainable, more hopeful ways of being human. I hope that by exploring these ideas through fiction, I and my fellow solarpunk writers can offer a vision of an aspirational future that we might all be inspired to work towards. ----- There are currently three other Berta stories available, exploring a few of these questions:

Helen Kenwright writes hopeful speculative fiction, and is currently working on a steampunk/solarpunk novel about history, humanity and unexpected consequences. She has an MA with distinction in Creative Writing from York St John University, and runs the Writing Tree, an organisation offering online creative writing tuition and support. She teaches creative writing for Converge, a project at York St John University which offers educational opportunities for people recovering from mental ill-health, and for the University of York's lifelong learning programme. Find more at www.helenkenwright.com or on Twitter at @hnkenwright

by Edward Edmonds To me, one of the most fascinating parts of the Solarpunk genre have been the discussions around technology and utopia; specifically, how we as humans can use technology to put us back into harmony with nature, rather than destroying it. The characters in “Grover: Case #C09 920, ‘The Most Dangerous Blend’” are placed in a world that has had to face this question and is still struggling with the answer. In the background of the story there is a world that has underwent a third world war. Our fascination with changing the weather led us to be able to manipulate it, which in turn, led to war and our own mass extinction. Now, twenty years later, people are picking up the pieces of society. However, that’s not the focus of the story; the story is a murder mystery that takes place at a weather manipulation facility. Our victim was torn apart by a large machine used to change the path of hurricanes, and the people in the story are often more concerned with deadlines and coffee rations than big issues. The technology changed so that we could still exist with the effects of climate change, but why didn’t we change more with it? Why didn’t we finally put our metaphorical big boots on, get to work, and build a utopia out of the wreckage of the old world? In short, we are human; we are the real toads in our imaginary gardens, to very loosely quote the poetry of Marianne Moore. We are often petty and short-sighted. We have ideals which we fight for, we have some days we won’t leave the couch, we love things, and we hate things. We’re not good or evil, we’re just complicated, and no amount of technology is going to change that. That might make a traditional utopia out of the question; and maybe it is, as without conflict, I think we’d get bored (doesn’t every good story have a conflict?). However, to me, if we end up with a world where we have made our mistakes, we have paid for them, and yet somehow, we managed to climb out of the wreckage of civilization, make a new civilization, and we are back in a place where we have kept our soul — as ugly and toad-like as that soul might be — we’ve won. The world I created is hopeful, not perfect, and as we move into an uncertain future, staring down climate change, I hope we manage to create a hopeful, if imperfect, world. Though, personally, I hope we don’t need to go through another mass extinction to get there. A native of Niagara Falls, Ontario, Edward Edmonds is a teacher currently living in Saskatchewan, Canada. His works have previously been published in the literary magazines Inscribed, Steel Bananas, and dead (g)end(er). You can find Edward on twitter @ededification if he's not haunting your local coffee shop.

by Jaymee Goh The title of my story comes from a meme I saw on the internet: “[your last location] of [your birthstone] and [current weather] = your next YA trilogy title” It was thus initially “A Baseball Field of Sapphire and Horrific Sun” but that didn’t really lend itself to a story. Hence “A Field of Sapphires and Sunshine.” What would be the sapphires in the sun, though? What glows like sapphires in the sun? Also, what would be unlike sapphires? I chose bluebottle flies. And why would these bluebottle flies be in the sunshine? What would they be attracted to? I chose dead bodies. * There are two stories from Malaysian folklore involving crocodiles that stick with me. In one, he is a greedy liar who is tricked into letting his prey go by the clever mousedeer. In another story, a family of crocodiles devour an old woman’s grandchild, who agrees to help the head crocodile’s grandchild in exchange for a promise to leave the river they live in. (The second story would become a foundation for my short story “Crocodile Tears,” published in Lightspeed Magazine.) Crocodiles are terrifying creatures, because of their propensity for ambush, their strength, and their looks. They’re giant lizards. They’re practically dinosaurs. And they would totally survive any man-made apocalypse. I had to have them in a story. There is, or was, a crocodile farm near my childhood home. The signs still say “crocodile farm” and for a time there was a seafood restaurant out there. I never saw it while it was a crocodile farm, but the memory stuck with me. I’ve had crocodile meat—I can’t decide if it has the texture of chicken with the taste of fish, or the texture of fish with the taste of chicken. It probably doesn’t matter because crocodile is crocodile. It is itself. Descriptions can try for approximations, but crocodile meat remains itself. And I love things like that, and writing about things like that. * I am not as much a fan of sunshine as I should be. I come from Malaysia, an equatorial country, hot and humid and sunshiney half the year before the monsoon rains come in. When I wrote the story, I lived in California, famed for its sunshine. I lived inland, in the desert, which was strangely more depressing than it should have been; I spent a lot of time indoors hiding from the sun because it was just so hot, and the sunshine so interminable, and the skies so blue with zero precipitation. I might have been a bit more favourably disposed towards the whole sunshine thing if I had seen more solar panels. *  Changi Airport Changi Airport I simultaneously love and hate airplane travel. I hate economy class on most airlines, which is a miserable state that is the way it is only because airlines are miserly and greedy for profits. When I lived in Halifax, Nova Scotia, I chose Malaysian Airlines because it had a 23-hour one-stop flight from Kuala Lumpur International Airport to Newark. It was a 2-hour flight from there to Nova Scotia. Also, it had decent food and really good in-flight entertainment. When I moved to California, I started taking Korean Airlines, from KLIA to Singapore’s Changi Airport, to Incheon Airport in South Korea, to Los Angeles. Changi has a butterfly room; Incheon… has free showers. Airline food quality and airport layover destinations became my top factors for choosing international flights after cost. But why go through all that if one could return to airship travel, slow but roomy? Does the specter of the Hindenburg still haunt air travel imagination? Imagine an airship envelope made of solar panels. Imagine the comfort of cruise travel in the air. * I was once bumped to business class. I was shocked at the full-service menu, ordered scampi and probably a margarita or two. I was served with porcelain plates, metal cutlery, and my drinks came in glasses. I stared at the Perrier bottle in the tiny bar next to my seat, appalled. In business class, I could recline my seat until I was horizontal. I cuddled up to watch a movie. It did not make me yearn to be rich; it made me yearn to eat the rich. * Unfortunately nobody eats the rich in my story. But CLOSE. Jaymee Goh is a writer, poet, reviewer, and scholar of science fiction and fantasy. Her work can be found in Lightspeed Magazine, Strange Horizons, and Science Fiction Studies. She is the editor of The SEA Is Ours: Tales of Steampunk Southeast Asia and The WisCon Chronicles Vol. 11: Trials by Whiteness.

by DK Mok Having grown up in Australia, I have a healthy respect for spiders. It’s a respect that occasionally veers into alarm if a furry huntsman spider scuttles across the bathroom ceiling, or if a leggy mystery spider peers out from behind the TV. However, over the years, that respect has turned increasingly into fascination and affection. It’s hard not to be charmed by splendidly dressed peacock spiders, especially when they’re described as weighing the same as a raindrop. Or to be intrigued by the diving bell spider which carries air bubbles to breathe underwater. I still remember the day I first heard the term "arachnologist" and decided it was one of the coolest titles a profession could have. More recently, I was awestruck when I read an article in National Geographic commenting that the ogre-faced spider has eyesight so sensitive that it can see the Andromeda Galaxy. In my short story "The Spider and the Stars", a young woman is equally struck by this captivating image and dedicates her life to investigating the diverse talents of not only spiders, but of all things creepy crawly. In particular, she’s compelled by the potential of biomimetics: developing new technologies inspired by the abilities and properties of living organisms. From termites and their climate-controlled monoliths to the complicated locomotion of spiders, nature is a sometimes brilliant, sometimes eccentric, engineer. Many of the challenges currently faced by humanity might be solved by taking a closer look at our planet’s tiniest inhabitants. Only a few years ago, it was discovered that the nanoscale pillars on cicadas’ wings have remarkable antimicrobial properties, which could pave the way for self-sterilising medical equipment. We often swat and spray and squish without thought, and it’s true, no one likes a plague, or an unwelcome visitor in the privy. But the more we learn about insects and spiders, the more we can appreciate the incredibly rich, complex and varied lives they lead. And, as our gaze turns towards distant galaxies, hopefully we’ll grow to understand how our own future is inextricably entwined with theirs. DK Mok is a fantasy and science fiction author whose novels include Squid’s Grief and Hunt for Valamon. DK has been shortlisted for four Aurealis Awards, two Ditmars and a WSFA Small Press Award. DK graduated from UNSW with a degree in Psychology, pursuing her interests in both social justice and scientist humour. DK lives in Sydney, Australia, and her favourite fossil deposit is the Burgess Shale. Connect on Twitter @dk_mok or www.dkmok.com.

by Gregory Scheckler My neighbors' chickens wander our backyard. And they're adorable. I used to give them individual names. Penelope liked me, and ran up to me whenever I did garden or yard work, until one fateful morning I found an explosion of feathers on our lawn: dead Penelope, killed by a fox. I was crushed. I began to wonder what kinds of proteins would be better, ethically, and how might they affect the people who live and work near them? Little by little, such questions became part of the background for my story "Grow, Give, Repeat" featured in the anthology Glass & Gardens: Solarpunk Summers. What is the future of food? While writing the story, I researched developments in cultured meat (a.k.a. lab-grown meat). It's a surprisingly robust field. There's a wonderful, quick overview article at NPR: "Lab-grown Meat a Reality, but Who Will Eat It?" (2008) One vexing problem is where does all the energy come from to produce cultured meat? The large energy costs of cultured meats could have much bigger environmental impacts than growing live animals. Some vertical farm designs resolve this problem by incorporating cycles of plant life with water-filtering pools fish for food. This cycling from one resource to another is the big design puzzle for farming in general, as much as for any mode of new, sustainable food production. So, in "Grow, Give, Repeat," I embedded the main character in design problems, and provided characters with a system that relied on overlapping cycles of resources. The history of such thinking goes back to at least the 1890s, when French chemist Berthelot imagined a future for synthetic foods. (See "Foods in the Year 2000" in 1894 McClure's). Berthelot believed that "Herds of cattle, flocks of sheep, and droves of swine will cease to be bred, because beef and mutton and pork will be manufactured direct from their elements." By the 1950s it was common for authors and film-makers to rely on "food pills" and other condensed forms of nutrition, especially for space travel or planetary colonization, such as in Ray Bradbury's Mars tale, "The Wilderness" (November 1952, the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction). From time-to-time, dehydrated foods like powdered drinks mixes (Tang!), edible algae and insects reappear as the great promise of sci-fi future foods. Sci-fi foods included the crushed insect bars in Snowpiercer (2013), cubbies of air-filtering and food plants in the series The Expanse (2012-), and the unforgettable talking cow who's happy to be eaten in Douglas Adams' Restaurant at the End of the Universe (1980).  Berthelot may not have been entirely wrong: new types of engineered foods have begun to appear in our local grocery store. My wife and I just tried a set of vegetarian burgers that were supposed to seem quite meat-like. It tasted like grilled cat food. And despite being made of pea protein, it was also very high fat, highly processed, and expensive -- not exactly healthy, nor good for ye olde household budget. And it was shipped a long distance to our store, which is not a good ecological solution. We have a long way to go before cultured meat is a reality. Meanwhile, food production intersects with local politics: a thicket of predicaments. While Berthelot may have imagined chemistry's contributions, he does not appear to have ever sat through a local zoning board meeting. In the story "Grow, Give, Repeat," political dynamics play out as social and economic unrest, including protests that directly affect the main character and her friends and neighbors. Her home town made some fairly stupid decisions, and some smart ones — just like we all do today. The real-world problems are big, but not impossible. Human population is increasing, but studied, practical solutions for better food production do exist. These include eating more plant-based foods, reducing use of food crops as biofuels, using drip irrigation rather than spray irrigation, and much more. A good introduction to how to feed our increasing populations can be found at National Geographic. But... do we have the social or political will to make such changes a reality? Massachusetts author-artist Gregory Scheckler crafts science fiction stories and cartoony artworks. His writings can be found at World Weaver Press, Crow's Mirror Books, the Berkshire Eagle, the Berkshire Review for the Arts, The Mind’s Eye, and Thought & Action. When he’s not writing or artmaking, he and his wife can be found skiing and biking the Berkshires, watching their neighbor's chickens, or tending their solar-powered home.

By Shel Graves Every year after I send in my taxes, I also write my representatives and let them know my spending priorities. Don't you? I figure if I can take the time to tell my government what my little piece of their budget is, I can let them know what I'd want them to do with it. In this troubling year, I found myself surprisingly focused. My letter was short with three points:

That last point is a great playground for optimistic science fiction. I love the power to imagine a better future. What's fun is that solar, of the moment, already seems sci-fi. It's an innovative and creative field. Harnessing the power of the sun, right? Even though I live in a rain-soaked city, it's not surprising I'm thinking solar. My good friend has been telling me about her work in the field. Women are innovating in sustainable energy (wrisenergy.org and powerhouse.fund), leading the solar sphere (seia.org and sepapower.org), and imagining a better today. Right now, teams of women are installing community solar systems at no cost. Meanwhile, I've been imagining far out utopian futures, "…the flickering light of a better world, for the moment accessible only through an act of imagination," as Ruth Levitas says in Utopia as Method. When I told a friend about my story forthcoming in Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers, he had to Google "solarpunk." Solarpunk is a term of this decade and hasn't yet taken its place in Merriam-Webster with steampunk and cyberpunk genres. It's fun to be pre-dictionary and joining the conversation about futures founded on renewable energies. However, as much as I'm excited by technology, as a devotee of feminist utopias (which focus on social and ecological futures), in my own imagining I don't look to scientific "stuff" to solve our problems. I always see transforming our selves — our ability to become more compassionate, empathic, connected — as the key to unlocking utopia. So, true to form, in my story "Watch Out, Red Crusher!" people provide the solar power and our relationships are what's at stake. The premise stretches the bounds of current tech, but I don't think it's that far-fetched! My story takes place during a summer festival and I was excited to read about this real life one — Utopian Acts. "Utopia is not a blueprint, but a conversation," say the festival founders. Agreed! Utopia, it's us: saying what we want and ever moving in that way. Shel Graves is a reader, writer, and utopian thinker who lives by the Salish Sea. She works as a caregiver at Pasado's Safe Haven, a non-profit on a mission to end animal cruelty. She earned her MFA in Creative Writing at Goddard College. She keeps her writer's journal at shelgraves.blogspot.com. Talk to her @Utopianista on Twitter and see pictures of her furry companions @Sheltopia on Instagram.

Website: http://shelgraves.blogspot.com/  by M Lopes da Silva What is the future of libraries? Or, to phrase it another way, what will future libraries be? These questions are far too broad in scope and possibility than can be condensed into one brief article. But these were the questions that drove me to write my short story “Cable Town Delivery”. I have a long history with libraries. It began conventionally enough, the way most relationships with libraries do -- while applying for a library card. I was very young, but I remember the delight that would soar through me as I stepped over the crackly, creaky rubber pad of the security gate and into a limitless paradise of ideas. I have always loved words and stories and books; a library is a wonderful place dedicated to what I loved most. In my very early grade school years, there was a miniature library in the classroom that you could check out books from, but I remember being appalled at the horribly small amount of books that you could check out at once. I couldn’t be limited to a mere two books! So I briefly turned to a life of crime, stuffing illicit books in my backpack, reading them at home, then becoming too embarrassed about the theft to return them. I tried to hide the books among the ones that I already owned, but my greed knew no limits when it came to books, and as the shelves filled up almost overnight my parents got wise to my wicked ways. I had to return a lot of books the next day, but I also remember the teacher raising the classroom book limit a bit, which was nice. In middle school, I began to volunteer at a local library. Eventually, they offered me a paid job. I shelved books and helped people find books and even seriously considered a career in the library sciences for a good, long while until the siren song of higher education lured me to my pitiful demise upon the rocks of student loan debt. I write this now from the higher plane of those purgatorial souls waiting to breathe debt-free air again, should I ever find an exit. In college, I took a class taught by Imagineers, and my team’s final project was to design a library — something I’d already spent a good portion of my life deeply thinking about — and our presentation was highly praised. I loved the idea of designing a library. Which brings me back to the opening question of this article, and my solarpunk short story, “Cable Town Delivery.” My story is one possible answer to the question: what would libraries look like in a post-apocalyptic setting? When environmental conditions are extreme, and our previous centers of knowledge become decentralized, what might arise? My take on this is influenced in large part by the concept of bookmobiles or mobile libraries. People living in remote communities would likely find any source of news, entertainment, or practical (DIY-type) knowledge highly desirable. Books, music, and visual media are extremely valuable; I would argue that they can be priceless when hardships arise. And yet a library is also an important cultural hub that can, and should be used by members of the community to grow stronger; so I wanted Cable Town’s protagonist to become inspired by the spirit of a mobile library. At the end of the story, she gets to ask herself what I think is the most exciting question of all: how do you make a library without any books (or other media) to begin with? How would you make a library in a scrappy outpost town without any media? What would you create or collect first? I have some thoughts, but there are so many ways to go with this! I’d love to hear yours in the comments. M. Lopes da Silva is an author and fine artist living in Los Angeles. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Electric Literature, Blumhouse, The California Literary Review, and Queen Mob’s Teahouse, and anthologies by Mad Scientist Journal, Gehenna & Hinnom Press, and Fantasia Divinity Publishing. She recently illustrated the Centipede Press collector’s edition of Jonathan Carroll’s The Land of Laughs. Find more at mlopesdasilva.wordpress.com.

by Jerri Jerreat At age 12, I leaned over the gunwale of the canoe and plucked a mussel shell out of a drowned tree. Inside, it was a pearly purple, a miniature shining world. This is what happens on a wilderness canoe trip. You discover a waterfall pouring in a trident over a tall monster of pink granite, or find yourself blinking at a thousand fireflies under a collection of stars shaped like a deer. I wish for such experiences for everyone, especially those growing up on the twenty-sixth floors or fleeing acts of war. “Camping with City Boy” has many inspirations, but wilderness trips in Ontario were foremost. I’ve taken thirteen-year-old feisty girls, family, and friends tripping. The being-shoved-in-a-cold-lake incident was inspired by a hotshot lawyer somewhere. If you’re from the prairies, the coasts, or south of the 49th Parallel, come on over. The towns of Haliburton and Bancroft are good places to aim. The steep wooded hills of Haliburton demand you ease your foot off the pedal to peek at blue water vistas. The Haliburton School of Art and Design is itself worth a visit. In Bancroft, you should become acquainted with blue sodalite. The artists and artisans in these towns have some kind of ancient magic, perhaps touched by their rocks and lakes. I haven’t been able to resist them. I deliberately set this story in that area. The residents of Bancroft who now sell freshly roasted pear soup beside slices of leopard rock and hand-knitted wool socks are quite likely to build a Skycity — tall condos connected by high parkland where they make electricity and grow food — in the future. They’re a resourceful people, spunky and good natured, this hardy mix of Algonquin and newer immigrants from Europe, Asia and the world. Makemba, the main character, would blend right in. Hope you enjoy the story. Jerri Jerreat's fiction has appeared in The New Quarterly, The Antigonish Review, The Dalhousie Review, and Room, among others. Another science fiction story appeared in an anthology Nevertheless: Tesseracts Twenty-One by Edge Publishing. Jerri is an Ontario paddler who has lived in Vancouver, Ottawa, St. Catharines, and in Tübingen, Germany. She now lives under a roof of solar panels on an ancient limestone seabed near Kingston, Ontario. Visit her website at jerrjerreat.com.

|

World Weaver PressPublishing fantasy, paranormal, and science fiction. Archives

February 2024

|

- Home

-

Books

-

All Books

>

- Beyond the Glass Slipper

- Bite Somebody

- Bite Somebody Else

- Black Pearl Dreaming

- Cassandra Complex

- Causality Loop

- Clockwork, Curses, and Coal

- Continuum

- Corvidae

- Cursed: Wickedly Fun Stories

- Dream Eater

- Equus

- Fae

- Falling of the Moon

- Far Orbit

- Far Orbit Apogee

- Fractured Days

- Frozen Fairy Tales

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Winters

- Grandmother Paradox

- Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline

- Haunted Housewives

- Heir to the Lamp

- He Sees You When He's Creepin': Tales of Krampus

- Into the Moonless Night

- Jack Jetstark's Intergalactic Freakshow

- King of Ash and Bones (ebook)

- Krampusnacht

- Last Dream of Her Mortal Soul

- Meddlers of Moonshine

- Mothers of Enchantment

- Mrs Claus

- Multispecies Cities

- Murder in the Generative Kitchen

- Recognize Fascism

- Scarecrow

- Sirens

- Shards of History

- Shattered Fates

- Skull and Pestle

- Solarpunk (Translation)

- Solarpunk Creatures

- Solomon's Bell

- SonofaWitch!

- Speculative Story Bites

- Trenchcoats, Towers, and Trolls

- Weredog Whisperer

- Wolves and Witches

- Anthologies and Collections

- Novels

- Novellas

- Fairy Tale

- Fantasy

- Romance

- Science Fiction

- Urban/Contemporary Fantasy

- Young Adult SFF

-

All Books

>

- Blog

- About

- Contact

- Press / Publicity

- Newsletter Signup

- Privacy Policy

- Store

RSS Feed

RSS Feed