Guest Blog by BrightFlame My story in Solarpunk Creatures, “Thank Geo,” is set in the Threads, the interconnected communities I write, and where I’d love to live. I first glimpsed the Threads during a trance journey led by my dear friend Starhawk—author, activist, permaculture designer—amidst a weekend workshop we co-taught. Participants worked with narrative to craft their stories for bringing forward just, resilient futures. We toured those futures during the imaginary journey, and I saw bits and pieces of what I’ve since fleshed out and named the Threads. Everyone is considered kin in the Threads since mutualism and interconnection across the Web of Life are foundational. While I picture the Threads in the far Northeast of Turtle Island, they could be anywhere. I’ve written more than a dozen stories set in the Threads, each exploring different timeframes and different problems and aspects of community. “Thank Geo” takes place about 150 years from now and brings in a very different character than the other stories. Humans connect to all kin through the Forest’s communication network courtesy of mycorrhizae. So all of my Threads stories have non-human characters, often trees and mycelium. “Thank Geo” is the first to bring in this particular form of kin. Indeed, “Thank Geo” explores the question, Who do we humans call kin? I’ve continued offering similar Storying the Future workshops to mundane and magical audiences because in order to create our desired futures, we need to first imagine them. I hope Solarpunk Creatures helps you tap into the solarpunk future you long for and inspires you to action. By the way, Starhawk has inspired me for decades. Have you read her novel The Fifth Sacred Thing and its sequel, City of Refuge? These are solarpunk from before we used the term. Starhawk not only writes solarpunk, she lives it. See Earth Activist Training. BrightFlame (she/they) writes, teaches, and makes magic for a just, regenerating world. Her fiction appears in Solarpunk Magazine and in several acclaimed anthologies, and her debut novel, The Working, is forthcoming from Water Dragon Publishing (Summer 2024). She’s known for her teaching in the worldwide pagan community and co-founded the Center for Sustainable Futures at Columbia University that features her nonfiction. Musings, doodles, and more at https://brightflame.com

0 Comments

Guest Blog by Jerri Jerreat Don’t go near there; it’s buggy (translation: rich in insect life) and dangerous (translation: fear of the unknown). I grew up afraid of wetlands, and thought swamps, bogs, fens, peatlands and marshes were all the same, hiding quicksand or crocodiles. Yep, here in Canada. One day I was portaging in a provincial park, Ontario, Anishnabeg territory, crossing a wood plank over mud. I glanced left. Between some willows was a ghostly area of trees, shrubs and wild grasses growing directly out of water, silvery green mossy plants hanging. The light fell differently in there. There were sparkles on reeds, birds racing across, splashes. Small voices spoke in keys and languages I did not know. It was where the fairies of my childhood lived.  “A swamp, eh?” commented the person behind me. “That’s a swamp?” I let them pass and stood, riveted. Recently I learned that over 40% of all plant and animal life begins or lives in wetlands. I saw a webinar by Toronto’s “Remediation Action Program,” (RAP.) They’ve been quietly restoring wetlands across the region. RAP has built rocky shoals, attached logs for turtles to rest on, planted indigenous marsh plants. They’ve worked on city streams and gullies, replanted the sides with native shrubs to hold the soil, removed invasive species, tires and plastic. One wetland had been drained and farmed for over a century. The new owner donated the field. RAP researched, then unblocked the original creek. Water flowed back in. By the end of the summer the field was a full, diverse wetland, a mix of heritage native plants. Seeds had lain under that field for over a hundred years, but had burst into life. By fall, researchers had spotted many species of water insects, and birds arriving. Imagine their wonder when they spotted the first frog, and then fish! Fish! Volunteers pulled out invasive plants, monitered it, and went further north to help the source creek. It made me want to dance. I’m a terrible dancer, lots of hand waving and hip shaking, no understanding of “what looks good on a dance floor.” But I love it, and regret that for adults, there aren’t enough places to dance. Community centres need to hold dances monthly. I digress. Last year the swarmy Premier of Ontario and his rich cronies nixed the position of the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario, (a non-partisan watchdog to uphold the Environmental Bill of Rights.) Then he cut the power of our Conservation Authorities and opened up the Greenbelt to allow for faster “development,” over areas that had been protected. Wetlands too. In Kingston, a rich forest had grown up bordered by a gorgeous wetland on a large property within walking distance of City Hall. Over 70 years ago a nasty factory had closed. The forest, it seems, has been healing the soil slowly. The City sold it all for a dime to a developer who wanted to clearcut the forest, (about 2000 mature trees), truck the topsoil away, cover it with clay and cement, and part of the wetland too. What for, you ask? Riverside condos and a yacht club. I protested to both levels of governments, of course, and was in a flotilla of canoes waving signs. I took many blurry photos of birds, turtles, the beauty of the area, and wrote letters. A group of scientists from Montréal suggested the paths be raised, and the small contaminated areas be fenced and planted to phyto-remediate them. Signs could teach people how bio-remediation works, and point out tree species, the nesting sites of a hundred turtles, and the names of the hosts of birds and creatures living there. The wetlands, absolutely teeming with life, should never be capped. In September 2022, after our many protests and petitions, Kingston City Council voted down the clearcut and condo scheme. I woke up one day with a sassy Wetlands dancing in my mind. She loved those geese and ducks, painted turtles and salamanders, and her friend, the Forest. She could be any Wetland threatened by developers. Maybe one near you. Maybe you could help her out. Jerri Jerreat’s writing, from Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee territory, appears in Grist/Fix: Imagine 2200 Climate Fiction; Flyway: Journal, Alluvian, Feminine Collective, Yale Review Online, The New Quarterly, Glass & Gardens Solarpunk Winters; Solarpunk Summers, & others. She has a growing pile of protest signs by the door & directs YouthImagineTheFuture.com. https://jerrijerreat.com/ Instagram: @jerrjtree

Guest Blog by Ana Sun Not long after I moved to the South Downs, a local friend told me how he used to associate the call of seagulls with summer holidays—but not since he’d lived here. It didn’t take long for me to grasp why: the novelty can wear off very quickly when you’re regularly and rudely woken up at 4 a.m. by avian disputes. Our seagulls—or just “gulls”, to be accurate—are notorious for their chip-stealing reputation. While there exists a good variety of birds in Brighton and Hove, gulls are possibly the most visible; they are certainly far from shy. They strut down Brighton streets, parade on the roofs of parked cars, scrutinise any passers-by carrying food with an accusing stare—as if you’ve taken what’s rightly theirs. You might also see carrion crows perched on lamp-posts or patrolling the beach, clusters of jackdaws and rooks in the parks, pigeons just about everywhere. The starlings on the Victorian remains of the West Pier are a wondrous sight to behold.  Brighton and its surrounds are one of the most progressive places I’ve had the privilege of living close to. It is presently the only place in the United Kingdom with a Green MP in Parliament; one of its constituents boasts the highest percentage of LGBTQ+ residents (20.11%) in the UK 2021 census. Unfortunately, it’s not a place untouched by inequality. Brighton also has a long-standing issue with drugs; until 2017, it had been one of the highest capital of drug deaths in England. Even such a progressive, inclusive city cannot be shielded from a failing national Conservative government that has run short of ideas—a government depriving local councils of much-needed funds by pitting them against each other, paralysing systems of social support. For me, being Solarpunk means doing the tough, emotional work of dreaming of a better world, a chance to explore possible futures that don’t shy away from the hard questions—such as how we might balance power within a community. I prefer grounding my Solarpunk stories in real places so we can imagine how an actual, physical location may one day be transformed. If you’ve lived within the vicinity of Brighton for some time, it’s impossible to escape the stories about the Whitsun weekend clash between the Mods and Rockers in 1964. (Even today, there are still popular shops selling Mod attire in the North Laine.) The iconic battle on Brighton’s beaches was just one of a series of fights that exploded in seaside towns across the south coast of England that year—an event seared into local imagination and lore. Painted as the “turmoil of contemporary youth” by the media of the time, the general perception now seems to accept that the coverage then may have exaggerated the scale and extent of the conflict. In one of my random rabbit-hole tumbles, I came across a video where a Mod recounted his memories of the period. His choice of words when describing the Rockers is riveting: “we saw them as being greasy, uneducated, unpleasant—they knew that.” A classic example of “us” vs. “them”—a study in tribalism. When I began writing “Night Fowls”, I was trying to process whether our ingrained storytelling mechanisms—especially the requirement for conflict—inevitably leads us to narratives that people who are unlike us can be reduced into obstacles that we must overcome. I also wanted to play out the challenges of a local government selected by sortition, unpack what happens when people have the best intentions, but still struggle to get it right. One day, it occurred to me that I could explore these themes with a story that harks back to that senseless 1964 Brighton battle—through the lens of our local birds. After all, they don’t always get along, certainly not at four o’clock in the morning outside my window. And then, there’s the question of our place among nature: what right do we have, to consider ourselves the most exceptional species in comparison to all others? This plagued me for months, while the ending of the story hung unfinished, useless and unsatisfying—until I found myself face-to-face with a red deer skull and antler headress from about 9000 BC. Seeing ourselves as separate from nature is a relatively recent phenomenon. Like us, the flora and fauna that grace us with their presence—are also made of star-stuff. Ana Sun writes from the edge of an ancient town along the River Ouse in the south-east of England. She spent her childhood in Malaysian Borneo and grew up living on islands. In another life, she might have been a musician, an anthropologist—or a botanist obsessed with edible flowers.

Guest Blog by Commando Jugendstil and Tales from the EV Studio There are plenty of stories, from Space Odyssey, to Terminator and the Avengers, in which AIs are a threat to humanity, and a fair amount in which AIs are the salvation of humanity, instead, deity-like caretakers who make choices on behalf of humanity for their own good. Collectively we dislike both options. The first one is a bit cliché at this point, and the second one is too closely aligned with the techno-utopianism proposed by many AI peddlers, made of technocratic solutions imposed on people by "experts" with no democratic oversight, with the underlying idea that humanity is too stupid, selfish or evil to be left to self-govern and that society must be optimized according to "scientific" and "rational" lines with a hefty dose of surveillance and manipulation. We're not buying what they're selling, thank you very much. There's plenty of good stories to be written about the resistance to such "benevolent caretaker" AI, but that was not the kind of story we wanted to go with for this anthology and so we ruminated and procrastinated, until one Saturday afternoon. The idea of this story came to us all at once in a café in Oxford. The main members were having a break with one of our silent partners, who is a researcher in the humanities. We started talking shop about our respective day jobs, about grant proposals, projects and coursework, and eventually the discussion started to veer towards digital humanities and the slow creep of AI into everything. From there, between scones and absolutely killer mocha coffee, the conversation devolved into giggles and speculation: why did Ultron flip the lid as soon as they saw the Pope online? What is the relationship between Ultron and Futurama's PreacherBot? What would happen if consciousness emerged not in an autonomous weapons system or in a resource management entity, but rather in an academic AI? And a digital humanities one, at that? Our silent partner provided the name, a good Arcadian one, and the rest of us retrofitted a plausible acronym. Soon LIN.C.O. was born, with their deep love for poetry and sheep, and their desire to "be a real person" to fulfill their dreams of nomadic pastoralism. Part Wall-E and part Pinocchio, LIN.C.O. is a relatable little ball of anxiety and innocence, who, like every other person in the world, is trying to figure out what they want from life and what is their place in the grand scheme of things. What we really wanted to write about was a quest for self-actualisation, and a society where every person, human or not, is allowed to self-actualise and become what they want to be, without discrimination and economic barriers, and we enjoyed every moment of it. While in the real world machine learning algorithms (incorrectly called AI) are tools of capitalist appropriation of the digital commons, of surveillance, and of commodification of human cultural production and creativity, wielded by techno-feudal corporations, we can imagine a different future where they are used to the benefit of people and under their democratic control and oversight. And yes, even one where people come in all shapes and sizes, not all of them necessarily made of cells and carbon, and yet everyone has the same rights to enjoy life to the fullest. We would say we deserve this. Commando Jugendstil is a solarpunk creative collective. Their projects merge technology and art with the idea of transforming the city into its sustainable version, while focusing on co-designing solutions with local communities, to stimulate a just transition that can spark from the ground up.

Tales from the EV is a small collective of storytellers. They fell in love with solarpunk while helping the Commando write Midsummer Night's Heist. Their collaboration has been going strong ever since. Members of TftEV are involved in climate justice activism with XR UK and the GNDE campaign.  Guest Blog by Kai Holmwood When I first read Joan Didion’s “On Morality,” what stuck with me wasn’t the point she was making, but the atmosphere of the desert in her writing. Somehow, in that essay nominally about morality, she captured the way I always felt while camping in Death Valley or the Mojave or the Sonoran on July road trips with my dad as he whispered in my ear of animals I’d never see and pointed out tire tracks, which he claimed would take a hundred years to fade, scarring the otherwise seemingly untouched landscape. “On Morality” might be the only piece of writing I’ve read that reproduces the feeling of the desert in the way I remember experiencing it. One line in particular from that essay stuck with me: Didion writes of the “graphic litanies of the grief awaiting those who failed in their loyalties to each other.” As someone growing up in the era of climate change, I always heard that line on a broader level, in the sense that we—by which, in this case, I mean to include myself in the globally privileged who disproportionately contribute to climate change while remaining disproportionately unaffected by it—have failed in our loyalties. Now we—the broadest possible “we,” all of us, human and nonhuman alike—are facing litanies of grief as a result. When you grow up in California, you can’t help but develop some instinctive fixation on water. There’s the ocean, of course, in its sunny southern laughter and its crashing northern grief. There’s the seemingly constant drought. There are the helicopters scooping water from nearby lakes to dump on wildfires. There are dusty signs by the highway announcing “NO WATER = NO JOBS.” There’s the constant uproar about a certain company bottling and selling mountain water even as the parched state wilts. As a fifth-generation Californian, when I think of the future, I think first and foremost about water. The issue of water, the feeling of Joan Didion’s desert, and the question of those failed loyalties to each other all swirled together in my mind into one image: the Sonoran Desert, personified, trying to save herself in a world that has abandoned and betrayed her. The question, of course, was what would happen if we fundamentally honored our loyalties to each other, human and non-human alike. What would happen if, in some future we might still reach, we chose to work with the desert instead of fighting against it? What if the human “we” chose loyalty, even to seemingly inhospitable environments, over self-interest? “Sonora’s Journey” offers one imagined answer. My playlist while writing this story (approximately in order; I usually listen obsessively to one song at a time until I move onto the next section/song): Calling You (Jevetta Steele) Coming Back to You (written by Leonard Cohen, performed by Trisha Yearwood) Hold On (Tom Waits, performed by Madison Cunningham) Ballad of the Absent Mare (Leonard Cohen) Ice Age (Hawksley Workman) See the Fire in Your Eyes (Red Dead Redemption 2, performed by Gustavo Steiner)

Kai Holmwood, a fifth-generation Californian, has been a freelance nonfiction writer for over a decade. She recently completed a Master of Writing degree at the University of Canterbury. She, her husband and their two-toothed former street cat, Halloumi, split their time between New Zealand and Portugal.

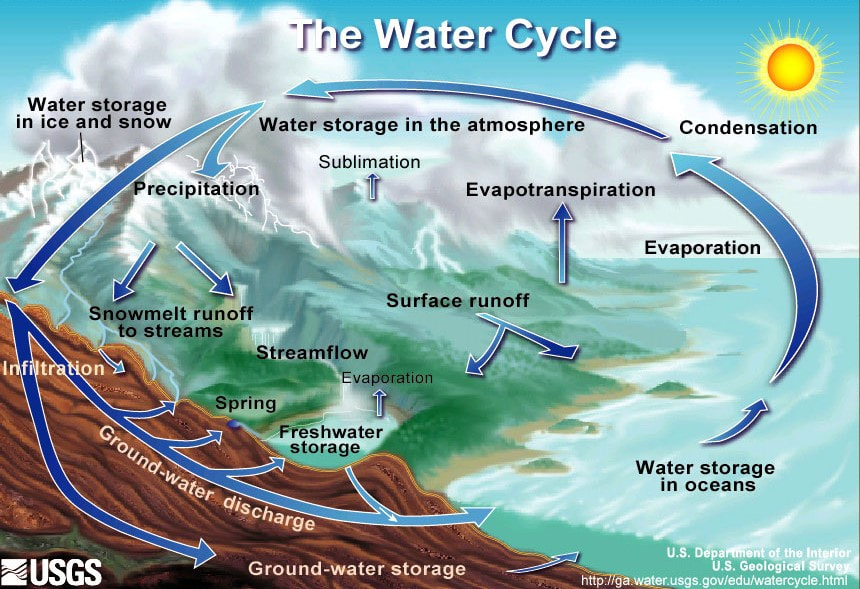

Guest Blog by Lauren C. Teffeau Water is life. But water doesn’t need life, thank you very much. Inorganic water will continue to exist whether humanity does or not, adopting different forms or chemical configurations, and outlast us all. Its indifference to us is matched only by our need of it, which some take as a mandate instead of responsibility. Water is memory. Or that’s at least what the writers of Frozen 2 would have us believe. But that begs the question what if water does remember what we do to it, the substances we commingle with it, how carelessly we run it down our drains? Water is as old as the universe, potentially recording all of humanity’s sins and accomplishments within its reservoirs. Water is cohesive. Cohesion speaks to the attraction water molecules have for bonding with more water molecules. Like seeks out like. But what if that process resulted in not just a bond between hydrogen atoms but also an exchange of information? What if water was some kind of superorganism, parts of it drifting away from the whole, only to return with tales of its experiences to share with the other water molecules? Such were the thoughts I had when writing my short story “Water Cycle” for the Solarpunk Creatures anthology. In it, I wanted to explore what water’s perspective on humanity might look like, separating it into three parts: the past, the present, and the (hopeful) future. I also wanted to ensure I included water in various states of matter and at all the different points of the water cycle. I had a lot of fun writing water as a collective entity, somewhat alien in its inorganic-ness, directly addressing the reader and by extension the whole of humanity. Needless to say it was therapeutic—like a solitary dip in a pool that’s the perfect temperature or an ice cube sliding over skin on a hot day—to imagine water as an unwilling witness to all of our mistakes, gradually growing curious about our actions over millennia, taking measure of our shortcomings but still rooting for us to meet our potential. Not quite ride or die, like a trauma-bonded lover, but there is a fundamental negotiation of obligation throughout the story, exploring the dialectical relationships between mortality and immortality, individualism and collectivism, using and being used, and above all water within and without. Water wants us to know it will be fine without us, but what if we all could be more? Lauren C. Teffeau is the author of Implanted (Angry Robot), a cyberpunk/solarpunk adventure shortlisted for the 2019 Compton Crook award for best first SF/F/H novel. Her climate fantasy novella A Hunger with No Name from University of Tampa Press releases Fall of 2024. Please visit laurencteffeau.com for more information.

Guest Blog by Badlungs Art About one year and a half ago I dived into the world of solar cooking, a tangible and exciting way to implement bits of solarpunk ideal to my everyday life. I fell in love with this low-tech approach, which is quite convenient to use in our sunny Southern France, and even made an Instagram account to share my recipes and experiences (https://www.instagram.com/sollies_cheese/). It was only a matter of time before this enthusiasm broke through in my art, and I did it the best way I know: with cute animals. The little mouse in her bright clearing in the middle of the forest might look adorably old-timey and send cottagecore vibes, but she demonstrates how easily dinner can be heated with a couple of mirrors and a black pot. Sometimes, future lies in simplicity. Since finding the right spot and angle for optimal heating quickly becomes one of the main obsessions of solar cooks all over the world, in both others illustrations I picked animals who have a special talent for basking in heat and sunlight and gave them tasks they might enjoy. Makis Catta could prove themselves the ideal assistants for this job by providing the perfect angle for a solar oven: they are so used to exposing their white bellies to the Sun like some kind of fluffy cult, it wouldn’t even feel like working to them. Just like people in Ancient times followed the traces in nature to know where to find sunlight, food or water, the first step towards a solarpunk way of life is to hush and observe nature, and enjoy animals’ instinctive wisdom. Finally, to make sure someone patiently watches after the food that is cooking, why not get the help of some cute and chonky bearded dragons who would be more than happy to lounge in the sun until lunch is done?  All three illustrations represent a different type of solar cooker. The mouse has a parabole-type cooker that can be both powerful and versatile. You have to check them out often and change the angle every half-hour, and preferably use a dark lid to prevent burning. The bearded dragons use a dark glass tube with reflectors, a contraption that might take a little longer to reach full heat but once it’s hot, it has a really nice inertia and keeps the food hot for a long time, even if the clouds show up. The lemurs use a box type oven that can be used in a similar way than a traditional gas or electric oven. They don’t heat up as much as others but make amazing slow cookers and zero energy crock pots. But there are so many more options available, and I’ve found myself heating veggies in the sun during summer with a windshield sunshade, an old baby bathtub and a black painted glass jar… Talk about one exciting way to take baby steps towards the future! It seems rather impossible for me to envision a solarpunk utopia without non-human animals, as their kingdom is one of the most essential parts of this balance we, dreamers, aim for. They also happen to be one of my favorite subjects to draw, so they are my most usual mode of expression. However, more than a personal preference, I feel that making solarpunk illustrations that include animals, such as those one can find in children books, is the best way to reach and to be appealing to a wider and younger audience of dreamers, to plant the seeds of a future where the Sun can be at peace with Earth, and provide his useful, gentle warmth, instead of an apocalyptic disaster. This is what I've been trying to convey with these illustrations, how what humans feel obligated to describe in progressive terms such as solarpunk, is precisely what most animals have been doing since the world started spinning. We just need to embrace our inner lemur instinct, and use our human intelligence to make it a hopeful future. Badlungs Art is an illustrator and tattoo artist from Southern France with a passion for solarpunk. She tries to convey it sometimes through her art, and by solar cooking on a regular basis, trying to get the best of Provence's sun, which was the main inspiration for the pieces published in this anthology.

Guest Blog by Rimi B Chatterjee Hi, I’m Rimi B. Chatterjee, and I’m a screenwriter, storyteller and academic based in Kolkata, India. Since 2005 I’ve been working on the Antisense Universe, a storyworld focused on climate action and civilisational redesign. The story arc is vast and spans from the Nineties to the twenty seventh century, covering the entire globe and near space, eventually also involving Venus. This story, Hopdog, is set circa 2080 in the Tarim Basin, after an apocalypse has destroyed the framework of our current civilisation and corporate power-structures are running a kind of post-feudal racket whereby they enslave everyone and party in the ruins. However, a group of Survivors who were thrown away in the desert have built a new kind of civlisation in their underground settlement called a survivarium, and they are now populating the survivarium with people and animals they are rescuing from the corporate slave camps. Peaches, the dog in my story, is one such rescue, along with the woman Peaches and her fellow dog-slaves were supposed to kill. That woman, who is called Queen Bitch in the story, is one of the major characters in the Antisense Universe, but I won’t tell you who she is to as to avoid spoilers. The first survivarium is called Zigsa’s Nest, because the philosophy of Antisense and its ethical system, karma, are invented by Zigsa, a teenage Tibetan who escapes from a test-to-destruction lab in Lop Nur and treks through the desert to the Flaming Mountains. I described her journey in ‘Arfabad’, which came out in Multispecies Cities: ‘Hopdog’ is kind of a sequel to ‘Arfabad’.  Zigsa is rather unusual: she has a mission. She begins calling the Survivors to her, at first through their dreams, and later through the Karma Sutra, a manual of how to build a survivarium. The survivariums exist to protect and nurture the ten treasures: people, animals, plants, soil, air, water, light, love, knowledge and karma. Zigsa and her friends create a network of underground activists called rootkittens who inflitrate the service territories to recruit and rescue new Survivors, so that they can go out into the wilderness and use the Karma Sutra to build survivariums of their own. The point of Antisense is to find a new way to organise work, reward happy-making actions and keep people safe, healthy and joyful. The Survivors do this by replacing the law and money of hanyo town with karma. The principle behind karma is this: it is a way of saying thank you. When the Survivors first gathered in their cave, many were sick of mind and body. If others had not fed, healed, comforted and warmed them, they would not have survived. Because their memories were full of holes, they used coloured threads they stole from a corporate shipment to keep track of everyone’s happy-making activities. These threads were in ten colours, each representing a particular kind of happy-making activity: healing, feeding, building things, tending the plants they begin to cultivate under stolen whitelights, scooping out new caves to accommodate newcomers. This tenfold division was because the rules and goals of breaking rock are a bit different than those of conversation or healing wounds. More details about this system can be found on my site antisenseuniverse.org. Once the Survivors have established the basis of their civilisation, and a group of miners among them have dug down and hollowed out the space for the survivarium, the Survivors began scouting for the ten treasures to place in their new home. They creep into the corporate cities, steal the animals out of zoos and the trees and plants from under biodomes. Because the story is told from Peaches’ point of view, I could not introduce you to Zohra, the six-foot-tall trucker who engineers Peaches’s rescue in the sixteen-wheeler truck used to transport the dogs to the fighting arena. But don’t worry, Zohra’s story will be told elsewhere. The core of Antisense is this: what would a truly good world look like, and how would it work? Who would live in it, and what would their day-to-day routine of work and play be? How would children grow, and how would people’s lives change when they’re old? What would they eat, and how would they dispose of waste? What would their systems for righting wrongs look like, and how would they treat victims and wrongdoers? How will they treat animals and nature? All of these questions are answered in the Antisense Universe, notably in the Karma Sutra which is 80 per cent written. In the coming days, I hope to write and publish more stories that will showcase this world, and eventually, make a series of animation films that will cover the whole story arc. Rimi B. Chatterjee is a screenwriter, novelist and academic based in Kolkata, India. She is currently developing the Antisense Universe, a storyworld focused on civilisational redesign and climate action, in which this story is also set. Eventually she hopes to produce a series of animation feature films set in this world.

Guest Blog by Andrew Knighton Writing a story always involves iteration, trying different versions of characters, plots, and wording. Usually, that stuff stays hidden, old versions disappearing into the darkness of the writer’s drafts folder. My Solarpunk Creatures story, The Business of Bees, was the second complete variation on a story with the same core idea but completely different execution. I was fond enough of that previous story, A Conspiracy of Pigeons, to share it on my blog, but not enough to submit it to the anthology. So in the name of letting other people learn from my mistakes, let’s look at the similarities and differences between these stories, and why I didn’t stop at the first one. What’s the Same?The first similarity is the protagonist. Both of these stories are told from the point of view of a cat, named Leo in Conspiracy and Luna in Business. Both cats are curious and adventurous. The structure of the two stories is pretty much the same. Our hero sees creatures in their city doing something strange, follows them to find out why, and discovers something unexpected that challenges our models of how nature fits into human society. There’s some similarity of setting. Both stories take place in a future where humanity has dealt with the self-imposed problems of climate change. But the specifics of those cities are where things start to diverge… What’s Different?Leo’s city is one abandoned by humanity, left to rot as an example of past mistakes. The humans live in shining cities visible on the horizon, but that’s not where the story takes place. Leo’s landscape is a ruined one. Luna, on the other hand, lives in one of those shining cities. The landscape she explores is an illustration of how we might build better, with renewable energy and rooftop gardens. Hope is all around rather than over the horizon. This change is mirrored in the creatures the cats are following. Leo is pursuing pigeons, which are, rightly or wrongly, widely seen as unclean pests. Luna, on the other hand, follows bees, symbols of industry and cooperation, insects we increasingly idealise as we recognise their importance to our environment. The result is a story that, while similar in its structure and message, has a very different tone. Why the Change?So why write the second version? And if that was what I submitted to the anthology, why publish the first one? I wrote A Conspiracy of Pigeons to fit the Solarpunk Creatures call for stories – something animal centred set in a solarpunk future. But while I was happy with the story, and it technically filled the brief, I could tell straight away that it wasn’t right. Sure, the humans of that setting live in a solarpunk future, but Leo doesn’t. His exclusion from it sets a dark tone, when people read solarpunk for brightness and hope. So I took what I had and thought about how I could keep the suitable bits while ditching the rest. That led to The Business of Bees, which fits the anthology brief in a meaningful way, not just a technical one. It’s designed to match readers’ expectations, which will mean a more satisfying read. Still, I liked Conspiracy. I liked Leo. I thought his story was worth reading, and different enough from Luna’s for both to exist in the world. So now there are two stories, and a lesson for me, maybe even for you. When you’re writing a story, think about tone and emotion, about how you’ll match the needs both of editors and of readers. Just because a story is good doesn’t mean it’s the right one for the moment, and just because it’s not right now doesn’t mean it needs to go to waste. Andrew Knighton has been writing for longer than he likes to admit, creating short stories, comics, and the fantasy novellas Ashes of the Ancestors and Silver and Gold. He lives in Yorkshire with an academic, a cat, and many unread books. Find him at andrewknighton.com and on Mastodon as @[email protected].

Guest Blog by Justine Norton-Kerston How did you and Aster come together on this journey? What is the history of your relationship? Aster’s my best friend and always will be. We grew up in Cottonwood Cove. So I guess I’d have to say our bond began in our youth. We were both restless kids, eager to explore the vast unknowns beyond our settlement. We'd often sneak out to stare at the horizon, promising each other that someday we'd find the mysteries hidden out there in the beyond. The tale of the prickly pears was a favorite legend passed down in our community, one that always captivated us. As we grew older, our sense of adventure only intensified. When the elders spoke of the Grand Canyon and the myths associated with it, we decided it was time to uncover the truth ourselves. Driven by curiosity and the allure of discovery, we embarked on this journey together. But our history isn't just about shared adventures—it's about mutual trust, respect, and a deep understanding that we're better together. In many ways, this journey was an embodiment of the promises we made as children, staring at that horizon. From what I’ve heard, the Colorado River boat ride seemed intense. What was going through your mind during that experience, and how did you manage to navigate the rapids? Yeah the Colorado River ride was unlike anything I've experienced. As we approached the rapids, my heart raced and a blend of excitement and fear took over. The immense power of nature was on full display, and it was terrifying. How could you not have an awe-inspiring respect for it? I remember thinking of our ancestors, who navigated waters like these without modern tools or knowledge. My main focus was on keeping us safe and ensuring we didn't capsize. I've had some experience with watercraft, but nothing quite this challenging. Every drop, twist, and turn of the river demanded split-second decisions. Since we weren’t all that familiar with most of the river, it all came down to trusting my instincts. Aster's presence was grounding. We communicated constantly, alerting each other to upcoming obstacles and adjusting our course. There were moments of sheer panic, but also exhilaration. Making it through those rapids reinforced our bond, and also reminded me of the unpredictability of nature—the importance of honoring it. Through it all, I held onto the hope that what lay beyond the tumultuous waters was worth the risk.  Picture by Justine Norton-Kertson Picture by Justine Norton-Kertson How did you come to be in the company of Jack, the hare? What's the story behind your unique bond? Ah, Jack! That little bunny has been a bundle of surprises since day one. It was actually during one of my solo expeditions in the outer regions of Cottonwood Cove that I stumbled upon a burrow, collapsed from what seemed to be a minor land shift. Digging through, I discovered a young rabbit, alone and petrified. How could I just leave him there? I named him Jack, after an old legend my mother used to tell me about a kid who climbed a giant beanstalk and explored the heavens. Over time we developed a bond, a silent understanding. Ever since the Grand Canyon expedition, Jack’s become my constant traveling companion, proving himself invaluable. You see, Jack has an innate ability to sense changes in the environment, often alerting us to potential dangers or leading us to needed water sources. He's more than just a companion—he's a partner in our adventures. Jack's keen instincts combined with Aster's resourcefulness and my experience make for quite the team. In that sense, the Grand Canyon journey wasn't just about discovery; it was also about the friendships we forged along the way, with Jack being one of the most unexpected and cherished. What did you learn about yourself and your companions throughout this adventure? What message or lesson would you like to share with others based on your experiences? Throughout this journey, I've come to realize that the world is filled with hidden wonders, and sometimes they lie beyond our preconceived notions and fears. I've learned that I'm more resilient than I ever thought, but more importantly, that resilience is amplified when shared with companions. With Aster's strength and Jack's instincts, we each brought unique attributes that not only complemented but elevated one another. This adventure reinforced that, individually, we each have our strengths, but together, we form something greater. The message I'd share is to never underestimate the value of collaboration. And be open to the unexpected. Sometimes, the most profound discoveries aren't just about places or things, but the relationships we create and the understanding we gain about ourselves and those around us. Embrace the unknown with an open heart and mind. And always remember, even in a world filled with knowns, there's still room for wonder, hope, and the possibility of finding the unexpected. That’s a beautiful sentiment. Are there any other legends or places you're interested in exploring next? Absolutely! Our world’s a tapestry of stories, myths, and wonders. After discovering the truth about the prickly pears, I've become even more intrigued by the tales of our ancestors. There's a particular legend about the "Whispering Sands" far out to the northwest—vast dunes said to hold the secrets of ancient civilizations. The sands are believed to murmur stories to those who listen closely. I've also heard tales of a hidden oasis, a paradise amidst the desert where rare flora and fauna thrive. Aster, Jack, and I have discussed the possibility of charting a course there someday. But beyond specific legends, it's the allure of the unknown that truly captivates me. The thrill of stepping into uncharted territories, of rewriting the narratives we once believed to be set in stone. Every horizon hides a new adventure, and I can't wait to see what lies beyond the next one. Every journey, after all, not only unravels the mysteries of the world but also deepens our understanding of ourselves. And that, to me, is the true essence of exploration. Justine Norton-Kertson created Android Press and Solarpunk Magazine. Their debut nonfiction, UTOPIAN WITCH, is forthcoming from Microcosm Publishing. They’re producer and host of the genre podcasts Unimatrix Zero and Imagitopia, and associate producer for The 7th Rule. Justine was named one of 2023’s Grist 50 Fixers. They live in Oregon.

|

World Weaver PressPublishing fantasy, paranormal, and science fiction. Archives

February 2024

|

- Home

-

Books

-

All Books

>

- Beyond the Glass Slipper

- Bite Somebody

- Bite Somebody Else

- Black Pearl Dreaming

- Cassandra Complex

- Causality Loop

- Clockwork, Curses, and Coal

- Continuum

- Corvidae

- Cursed: Wickedly Fun Stories

- Dream Eater

- Equus

- Fae

- Falling of the Moon

- Far Orbit

- Far Orbit Apogee

- Fractured Days

- Frozen Fairy Tales

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Winters

- Grandmother Paradox

- Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline

- Haunted Housewives

- Heir to the Lamp

- He Sees You When He's Creepin': Tales of Krampus

- Into the Moonless Night

- Jack Jetstark's Intergalactic Freakshow

- King of Ash and Bones (ebook)

- Krampusnacht

- Last Dream of Her Mortal Soul

- Meddlers of Moonshine

- Mothers of Enchantment

- Mrs Claus

- Multispecies Cities

- Murder in the Generative Kitchen

- Recognize Fascism

- Scarecrow

- Sirens

- Shards of History

- Shattered Fates

- Skull and Pestle

- Solarpunk (Translation)

- Solarpunk Creatures

- Solomon's Bell

- SonofaWitch!

- Speculative Story Bites

- Trenchcoats, Towers, and Trolls

- Weredog Whisperer

- Wolves and Witches

- Anthologies and Collections

- Novels

- Novellas

- Fairy Tale

- Fantasy

- Romance

- Science Fiction

- Urban/Contemporary Fantasy

- Young Adult SFF

-

All Books

>

- Blog

- About

- Contact

- Press / Publicity

- Newsletter Signup

- Privacy Policy

- Store

RSS Feed

RSS Feed