Guest Blog by Ana Sun Not long after I moved to the South Downs, a local friend told me how he used to associate the call of seagulls with summer holidays—but not since he’d lived here. It didn’t take long for me to grasp why: the novelty can wear off very quickly when you’re regularly and rudely woken up at 4 a.m. by avian disputes. Our seagulls—or just “gulls”, to be accurate—are notorious for their chip-stealing reputation. While there exists a good variety of birds in Brighton and Hove, gulls are possibly the most visible; they are certainly far from shy. They strut down Brighton streets, parade on the roofs of parked cars, scrutinise any passers-by carrying food with an accusing stare—as if you’ve taken what’s rightly theirs. You might also see carrion crows perched on lamp-posts or patrolling the beach, clusters of jackdaws and rooks in the parks, pigeons just about everywhere. The starlings on the Victorian remains of the West Pier are a wondrous sight to behold.  Brighton and its surrounds are one of the most progressive places I’ve had the privilege of living close to. It is presently the only place in the United Kingdom with a Green MP in Parliament; one of its constituents boasts the highest percentage of LGBTQ+ residents (20.11%) in the UK 2021 census. Unfortunately, it’s not a place untouched by inequality. Brighton also has a long-standing issue with drugs; until 2017, it had been one of the highest capital of drug deaths in England. Even such a progressive, inclusive city cannot be shielded from a failing national Conservative government that has run short of ideas—a government depriving local councils of much-needed funds by pitting them against each other, paralysing systems of social support. For me, being Solarpunk means doing the tough, emotional work of dreaming of a better world, a chance to explore possible futures that don’t shy away from the hard questions—such as how we might balance power within a community. I prefer grounding my Solarpunk stories in real places so we can imagine how an actual, physical location may one day be transformed. If you’ve lived within the vicinity of Brighton for some time, it’s impossible to escape the stories about the Whitsun weekend clash between the Mods and Rockers in 1964. (Even today, there are still popular shops selling Mod attire in the North Laine.) The iconic battle on Brighton’s beaches was just one of a series of fights that exploded in seaside towns across the south coast of England that year—an event seared into local imagination and lore. Painted as the “turmoil of contemporary youth” by the media of the time, the general perception now seems to accept that the coverage then may have exaggerated the scale and extent of the conflict. In one of my random rabbit-hole tumbles, I came across a video where a Mod recounted his memories of the period. His choice of words when describing the Rockers is riveting: “we saw them as being greasy, uneducated, unpleasant—they knew that.” A classic example of “us” vs. “them”—a study in tribalism. When I began writing “Night Fowls”, I was trying to process whether our ingrained storytelling mechanisms—especially the requirement for conflict—inevitably leads us to narratives that people who are unlike us can be reduced into obstacles that we must overcome. I also wanted to play out the challenges of a local government selected by sortition, unpack what happens when people have the best intentions, but still struggle to get it right. One day, it occurred to me that I could explore these themes with a story that harks back to that senseless 1964 Brighton battle—through the lens of our local birds. After all, they don’t always get along, certainly not at four o’clock in the morning outside my window. And then, there’s the question of our place among nature: what right do we have, to consider ourselves the most exceptional species in comparison to all others? This plagued me for months, while the ending of the story hung unfinished, useless and unsatisfying—until I found myself face-to-face with a red deer skull and antler headress from about 9000 BC. Seeing ourselves as separate from nature is a relatively recent phenomenon. Like us, the flora and fauna that grace us with their presence—are also made of star-stuff. Ana Sun writes from the edge of an ancient town along the River Ouse in the south-east of England. She spent her childhood in Malaysian Borneo and grew up living on islands. In another life, she might have been a musician, an anthropologist—or a botanist obsessed with edible flowers.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

World Weaver PressPublishing fantasy, paranormal, and science fiction. Archives

February 2024

|

- Home

-

Books

-

All Books

>

- Beyond the Glass Slipper

- Bite Somebody

- Bite Somebody Else

- Black Pearl Dreaming

- Cassandra Complex

- Causality Loop

- Clockwork, Curses, and Coal

- Continuum

- Corvidae

- Cursed: Wickedly Fun Stories

- Dream Eater

- Equus

- Fae

- Falling of the Moon

- Far Orbit

- Far Orbit Apogee

- Fractured Days

- Frozen Fairy Tales

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Winters

- Grandmother Paradox

- Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline

- Haunted Housewives

- Heir to the Lamp

- He Sees You When He's Creepin': Tales of Krampus

- Into the Moonless Night

- Jack Jetstark's Intergalactic Freakshow

- King of Ash and Bones (ebook)

- Krampusnacht

- Last Dream of Her Mortal Soul

- Meddlers of Moonshine

- Mothers of Enchantment

- Mrs Claus

- Multispecies Cities

- Murder in the Generative Kitchen

- Recognize Fascism

- Scarecrow

- Sirens

- Shards of History

- Shattered Fates

- Skull and Pestle

- Solarpunk (Translation)

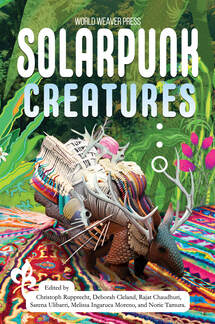

- Solarpunk Creatures

- Solomon's Bell

- SonofaWitch!

- Speculative Story Bites

- Trenchcoats, Towers, and Trolls

- Weredog Whisperer

- Wolves and Witches

- Anthologies and Collections

- Novels

- Novellas

- Fairy Tale

- Fantasy

- Romance

- Science Fiction

- Urban/Contemporary Fantasy

- Young Adult SFF

-

All Books

>

- Blog

- About

- Contact

- Press / Publicity

- Newsletter Signup

- Privacy Policy

- Store

RSS Feed

RSS Feed