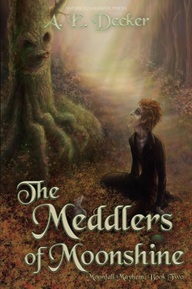

Guest Post by A.E. Decker If history is written by the winners, the winners in literature are the characters allowed to tell a story from their point of view. The Meddlers of Moonshine, the second book in the Moonfall Mayhem series, is due out later this month. Its imminent publication is making me think of the story that provided the strongest inspiration for it: Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw. The Turn of the Screw is the only story I’ve ever read that has unsettled me. You have to keep in mind that I’m the type of person who claps her hands when Montresor bricks Fortunato up in the vault in Poe’s “The Cask of Amontillado.” I’m weird like that. But even though The Turn of the Screw and “The Cask of Amontillado” feature unreliable narrators, Montresor never erases Fortunato’s voice. Every line of dialogue Fortunato speaks is recorded, allowing us to draw our own opinions of his character. In contrast, the governess in The Turn of the Screw never quotes the exact words of her charges, Milo and Flora, until the novella is halfway finished and she herself is already convinced that they’re communing with evil spirits. Of course, we the readers cannot be allowed a perspective other than the governess’ in The Turn of the Screw. A glimpse inside the mind of any of the other characters would instantly dispel the central mystery of whether the ghosts are real or a product of the governess’ delusion and spoil the effect of the story. So we’re left wondering: is the governess a good woman combating the forces of evil, or are these two children, already isolated and possibly abused, at the mercy of a crazed person determined to think the worst of them? To me, the latter proposition is far more terrifying than any ghost, and it was this interpretation which produced the central story in The Meddlers of Moonshine. There’s a scene early in The Turn of the Screw that cemented my opinion of the governess’ character. It’s quite early on, and on first reading, innocuous. The governess and her confidant, housekeeper Mrs. Grose, are discussing Milo. Flora is present in the room with them, eating dinner. The housekeeper has set her in a highchair, tied a bib around her neck, and given her a meal of bread and milk. Flora is eight years old. Now, I’m quite aware that the Victorian ideas of child-rearing were quite different from our modern day ones, but I’ve read other Victorian books and never encountered a scene so infantilizing to a child quite old enough to sit in a normal-sized chair and eat proper food with a napkin. Flora is not allowed to speak, of course, even when the governess and Mrs. Grose are discussing her. The scene has always reminded me of a child playing with a doll. The governess’ first meeting with Milo is remarkably similar. She comments gushingly on his appearance, but gives us none of his words or thoughts. Only when the children start behaving in a way she deems “improper” or “deceitful” does she report their words, and even then, we get the sense they have passed through the filter of her judgment. Toys are not meant to misbehave. That’s the real horror, to me; being under the complete control of a person who sees you as an object. True evil, as the immortal Terry Pratchett once wrote, starts with people viewing other people as things.  Authors have ways of getting their own back. My disquiet with The Turn of the Screw, and my interpretation that the priggish, self-righteous and delusional governess had tormented a pair of already tormented children — one to death — inspired me to turn my own screw, in a sense. I knew that one of the books in the Moonfall Mayhem series would parody the tropes found in Gothic fiction. I also knew that each of Ascot’s companions would be given a chance to share a book’s perspective with her in turn. Rags-n-Bones is easily the meekest and most innocent of Ascot’s companions, and since one of Gothic literature's main themes is of innocence confronting depravity, it seemed appropriate that this story was his to be told — in his own words. And, to balance the scales, I gave Milo and Flora their voices in the form of Kay and Lindsay Ashuren. Their backgrounds are not identical, but if there is a place where characters from books meet, such as in the works of Jasper Fforde, I like to think they’d recognize one another. There’s a touch of Frankenstein in Meddlers, too, and a trace of good old Dracula. But funnier. Rest assured; much funnier. I’ve made my peace with The Turn of the Screw now. I still love the story, even as it makes my flesh creep. Perhaps one day, I’ll even revisit it and sympathize with the governess, in which case, I’ll have to write another book exonerating her. Just don’t hold your breath.  A. E. Decker hails from Pennsylvania. A former doll-maker and ESL tutor, she earned a master’s degree in history, where she developed a love of turning old stories upside-down to see what fell out of them. This led in turn to the writing of her YA novel, The Falling of the Moon. A graduate of Odyssey 2011, her short fiction has appeared in such venues as Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Fireside Magazine, and in World Weaver Press’s own Specter Spectacular. Like all writers, she is owned by three cats. Come visit her, her cats, and her fur Daleks at wordsmeetworld.com.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

World Weaver PressPublishing fantasy, paranormal, and science fiction. Archives

February 2024

|

- Home

-

Books

-

All Books

>

- Beyond the Glass Slipper

- Bite Somebody

- Bite Somebody Else

- Black Pearl Dreaming

- Cassandra Complex

- Causality Loop

- Clockwork, Curses, and Coal

- Continuum

- Corvidae

- Cursed: Wickedly Fun Stories

- Dream Eater

- Equus

- Fae

- Falling of the Moon

- Far Orbit

- Far Orbit Apogee

- Fractured Days

- Frozen Fairy Tales

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Winters

- Grandmother Paradox

- Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline

- Haunted Housewives

- Heir to the Lamp

- He Sees You When He's Creepin': Tales of Krampus

- Into the Moonless Night

- Jack Jetstark's Intergalactic Freakshow

- King of Ash and Bones (ebook)

- Krampusnacht

- Last Dream of Her Mortal Soul

- Meddlers of Moonshine

- Mothers of Enchantment

- Mrs Claus

- Multispecies Cities

- Murder in the Generative Kitchen

- Recognize Fascism

- Scarecrow

- Sirens

- Shards of History

- Shattered Fates

- Skull and Pestle

- Solarpunk (Translation)

- Solarpunk Creatures

- Solomon's Bell

- SonofaWitch!

- Speculative Story Bites

- Trenchcoats, Towers, and Trolls

- Weredog Whisperer

- Wolves and Witches

- Anthologies and Collections

- Novels

- Novellas

- Fairy Tale

- Fantasy

- Romance

- Science Fiction

- Urban/Contemporary Fantasy

- Young Adult SFF

-

All Books

>

- Blog

- About

- Contact

- Press / Publicity

- Newsletter Signup

- Privacy Policy

- Store

RSS Feed

RSS Feed