|

By Sarena Ulibarri. Last summer at the Clarion Writers’ Workshop, someone asked our classmate from Singapore to describe what it was like where he was from. He raved about the amazing biodomes, and having never heard of such a thing, I did an image search on my phone. I showed him the pictures I found — lush gardens and waterfalls inside crystalline domes, massive “trees” that are actually made of solar cells, a building shaped like a lotus that collects and uses only rainwater. “Yeah, that’s my ’hood,” he said. “We live in the future!” I realized that all the futures I’d been writing about for the last decade or so were bleak, starved, oppressive wastelands. I took for granted things like “all the trees are gone” and “everywhere is overpopulated.” Why? A combination of the bleak future painted by real life scientists and politicians as they fought about environmental issues, and the bleak future painted by all the cyberpunk and dystopia science fiction films and books that I loved. But this is not the only kind of future possible, either in life or in fiction. When I joined World Weaver Press as an Assistant Editor in January, I wrote this about the kind of books I hoped to publish:

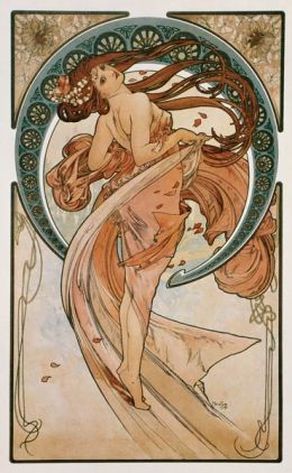

I had in mind those images of Singapore, but also rooftop gardens and urban farms, electric cars and creative public transportation, rural settings that still had the latest tech. I didn’t have a name for this kind of science fiction, though I’d heard a few terms tossed around: cli-fi, eco-fabulism, eco-fiction. But recently I came across the definition of a new subgenre, solarpunk, and I said, “This is it. This is exactly what I’ve been craving.”  Solarpunk is a science fiction subgenre depicting a society that has embraced sustainable energy sources such as solar and wind, and shows high technology co-existing with or even complementing nature. Part of what the “-punk” suffix means is a recognizable aesthetic — the terms steampunk, cyberpunk, and dieselpunk all conjure particular images and styles even for people who haven’t read these subgenres. The aesthetic of a solarpunk world is still being defined, but a favored suggestion is Art Nouveau, a style of art and architecture based on the shapes and colors of nature. A solarpunk world is not a utopia, but the subgenre does approach the twenty-first century’s biggest issues — climate change, energy production, urbanization, resource scarcity — with optimism. Solar energy is not perfect, and it may not be the only way or even the best way to free ourselves from fossil fuels — the production of solar panels still requires fossil fuels, after all, and solar energy is nearly impossible to store. But “solar” still works as a good symbol for something like solarpunk, because it represents the brightness of a potential future, and the freedom that could come if everyone had equal access a virtually unlimited resource like the sun. It’s the role of scientists and engineers to create new technologies; it’s the role of the science fiction writer to speculate about how those technologies may interact with people and culture. It’s too easy, sometimes, for the science fiction writer to be reactionary, imagining all the things that could go wrong with a new or proposed technology. After all, fiction needs conflict, right? The last hundred years certainly saw the development of some scary technologies, but it’s possible to move beyond fear without losing story conflict. Nuclear energy can create awful, destructive weapons. Know what else it can do? Fuel desalination plants to provide water to drought-stricken areas. Drones can be used in warfare, but they can also be used to identify animal poachers, or to provide supplies to disaster areas. The silica sand that’s used in natural gas fracking is also the main ingredient in silicon solar panels, and it’s one of the most abundant resources on the planet. One way to motivate change is to make it uncomfortable for people to be where they are — that’s the strategy of dystopia: if you continue on this path, look where we’ll end up. Another way is to make it comfortable for people to be where you want them to be — that’s the strategy of solarpunk: look at this beautiful world we could build. Can science fiction directly influence science or policy? No, nor should it. But it can influence what people see as possible, and what images people default to when they think of the future. I know I’m ready for brighter visions of the future. Sarena Ulibarri, WWP Assistant Editor, earned an MFA from the University of Colorado at Boulder, and attended the Clarion Fantasy and Science Fiction Writers' Workshop at UCSD in 2014. Her short fiction has appeared in Lightspeed,NewMyths.com, The Colored Lens, Kasma SF, and elsewhere. She currently lives in New Mexico with her husband and their Welsh Corgi. sarenaulibarri.com

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

World Weaver PressPublishing fantasy, paranormal, and science fiction. Archives

February 2024

|

- Home

-

Books

-

All Books

>

- Beyond the Glass Slipper

- Bite Somebody

- Bite Somebody Else

- Black Pearl Dreaming

- Cassandra Complex

- Causality Loop

- Clockwork, Curses, and Coal

- Continuum

- Corvidae

- Cursed: Wickedly Fun Stories

- Dream Eater

- Equus

- Fae

- Falling of the Moon

- Far Orbit

- Far Orbit Apogee

- Fractured Days

- Frozen Fairy Tales

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Winters

- Grandmother Paradox

- Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline

- Haunted Housewives

- Heir to the Lamp

- He Sees You When He's Creepin': Tales of Krampus

- Into the Moonless Night

- Jack Jetstark's Intergalactic Freakshow

- King of Ash and Bones (ebook)

- Krampusnacht

- Last Dream of Her Mortal Soul

- Meddlers of Moonshine

- Mothers of Enchantment

- Mrs Claus

- Multispecies Cities

- Murder in the Generative Kitchen

- Recognize Fascism

- Scarecrow

- Sirens

- Shards of History

- Shattered Fates

- Skull and Pestle

- Solarpunk (Translation)

- Solarpunk Creatures

- Solomon's Bell

- SonofaWitch!

- Speculative Story Bites

- Trenchcoats, Towers, and Trolls

- Weredog Whisperer

- Wolves and Witches

- Anthologies and Collections

- Novels

- Novellas

- Fairy Tale

- Fantasy

- Romance

- Science Fiction

- Urban/Contemporary Fantasy

- Young Adult SFF

-

All Books

>

- Blog

- About

- Contact

- Press / Publicity

- Newsletter Signup

- Privacy Policy

- Store

RSS Feed

RSS Feed