|

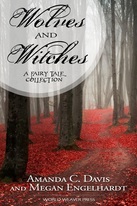

Amanda C. Davis, co-author of the fairy tale collection Wolves and Witches, shares why one of her favorite fairy-tale retellings works so darn well: I'm sure Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine's classic 1986 musical Into the Woods wasn't my first twisted fairy tale (that might have been something by Jon Scieszka) but it's the one that made the strongest impression, and it continues to impress me today. The music is complex but catchy. The lyrics are clever. Add a showstopping witch as a villain/plot catalyst/antihero and it's no wonder the thing has seen multiple Tony awards and successful revivals worldwide. As a fairy-tale retelling, I believe Into the Woods succeeds because it does the three things all retellings should: it understands the source material, it remakes it in an insightful way, and it adds its own value. Respect the Source The first line of Into the Woods is "Once upon a time." Its last line is " -- and happily ever after!" (Plus a tiny, tiny coda that sums up the musical's themes. More on that later.) Most of the characters are named for their roles: the Witch, Granny, the Baker's Wife. The first act spins together five separate tales -- one of them invented, but so pitch-perfect that it makes you wonder if you've simply never read it before -- and though they're performed with winks and wry smiles, they're played perfectly straight. The only twist is their combination, which is a pretty clever one, though increasingly common. The first act shows two things: that Sondheim got his inspiration from sources more reliable than Disney movies, and that he understands that the stories are sufficient, without change, to hold an audience's attention. Then the second act happens. Tear It Down Spoilers! It's entirely possible to watch the first act of Into the Woods and quit happy. Sure, there's a called-out "To be continued!" but that act, like the second, ends with " -- happily ever after!" It's a good stopping point for little kids or, perhaps, adults uninterested in shattering a pleasant illusion. The second act of Into the Woods deconstructs the very notion of "happy ever after" simply by noting that every story continues after the last page, and that stories tend to end with a major life change. Marriages have occurred. Children have been born. Adventures have been had that can't be forgotten. And though challenges have been overcome and wishes have been fulfilled, it's not in human nature to be satisfied where we are -- even as a queen. The consequences of previous adventures return with a vengeance, and that reshapes the fairytale endings of the original stories into ... something else. Sondheim and Lapine have thought critically about their characters and extended them beyond "THE END" in believable and sympathetic ways. So should all writers, but it's especially valuable in a retelling. Have Something to Say Fairy tales have always been metaphors. No child has ever really needed to be told not to waste time testing every bowl of porridge in a bear's house, or where to find a giant's heart. The best fairytale retellings not only extract meaning from the story, but they infuse it with meanings from the author's own heart. Into the Woods is about children and parents: their obligations to one another, the possibilities and agonies of their relationships. It's about awakenings (it includes Little Red Riding Hood -- how could it not?). It's about what we want and why, and what we do when we get it. As far as musicals go, it's thematically deliberate, even dense. The writers used these stories to tell their own stories. It's one of the things fairy tales do best. Fairy-tale retellings are popular, and no wonder; they're fun to do, with a wild variety of available tropes and excellent structures to build on. Of the three elements they really require -- knowledge, deconstruction, and purpose -- I think the last is the most difficult and most important. Granted, a faux-thoughtful "But what is the story SAYING?" is probably the one line that has ruined more young readers than anything else ever said in an English class. But readers who look for purpose won't be sorry, and writers who can effectively wield it -- those are the writers bridging fairytale worlds and ours, writing stories that matter, to them and to us. That's what makes Into the Woods, and all effective retellings, really sing. You can read Amanda C. Davis's new collection of fairy tale retellings with her sister Megan Engelhardt, Wolves and Witches, available now in paperback and ebook from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, and other online retailers.  Amanda C. Davis is a combustion engineer who loves baking, gardening, and low-budget horror films. Her short fiction has appeared in Shock Totem, Orson Scott Card’s InterGalactic Medicine Show, and others. You can follow her on Twitter (@davisac1) or read more of her work at amandacdavis.com.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

World Weaver PressPublishing fantasy, paranormal, and science fiction. Archives

February 2024

|

- Home

-

Books

-

All Books

>

- Beyond the Glass Slipper

- Bite Somebody

- Bite Somebody Else

- Black Pearl Dreaming

- Cassandra Complex

- Causality Loop

- Clockwork, Curses, and Coal

- Continuum

- Corvidae

- Cursed: Wickedly Fun Stories

- Dream Eater

- Equus

- Fae

- Falling of the Moon

- Far Orbit

- Far Orbit Apogee

- Fractured Days

- Frozen Fairy Tales

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Winters

- Grandmother Paradox

- Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline

- Haunted Housewives

- Heir to the Lamp

- He Sees You When He's Creepin': Tales of Krampus

- Into the Moonless Night

- Jack Jetstark's Intergalactic Freakshow

- King of Ash and Bones (ebook)

- Krampusnacht

- Last Dream of Her Mortal Soul

- Meddlers of Moonshine

- Mothers of Enchantment

- Mrs Claus

- Multispecies Cities

- Murder in the Generative Kitchen

- Recognize Fascism

- Scarecrow

- Sirens

- Shards of History

- Shattered Fates

- Skull and Pestle

- Solarpunk (Translation)

- Solarpunk Creatures

- Solomon's Bell

- SonofaWitch!

- Speculative Story Bites

- Trenchcoats, Towers, and Trolls

- Weredog Whisperer

- Wolves and Witches

- Anthologies and Collections

- Novels

- Novellas

- Fairy Tale

- Fantasy

- Romance

- Science Fiction

- Urban/Contemporary Fantasy

- Young Adult SFF

-

All Books

>

- Blog

- About

- Contact

- Press / Publicity

- Newsletter Signup

- Privacy Policy

- Store

RSS Feed

RSS Feed