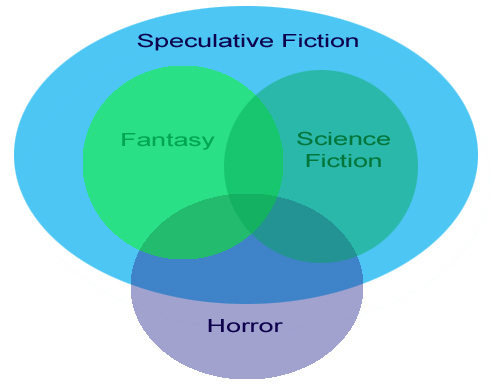

Top photo credit: “?” by Carlez on Flickr. Top photo credit: “?” by Carlez on Flickr. At World Weaver Press, we publish speculative fiction — but just what is spec fic? The definition is simple: fiction possessing elements that aren’t feasible based on modern technology or ones that cannot be explained by modern science. This includes magic, ray guns, the supernatural, premonitions, downloading your consciousness into a computer, AI, talking to ghosts, time travel, clockwork beings, alien life forms, ships that hop and skip around the universe, and just about anything that we don’t have a ready answer for. Speculative fiction is a catch-all term. Instead of having to sub-divide science fiction from fantasy (or define its hybrid baby, science-fantasy), separate high fantasy from urban fantasy, to parse out magic-based systems from non-magic systems, and try to figure out just where “weird stories” end and slipstream begins, we can just say it’s speculative fiction. Having a term to encompass everything makes sense: rarely have I found a fan of science fiction and fantasy who will only read a certain subset of the genre. Genre readers read, read a lot, and read across boundaries. The bookstores understand this. They don’t keep the science fiction away from the fantasy; they’re all mixed up on the same shelves. Surprisingly, I’ve heard people disparage the use of the term “speculative.” Some of these people believe that the term is an attempt to sanitize genre fiction of its less-than-highbrow historical association with the pulp press, or that it’s an attempt to bring sci-fi into the mainstream. Others believe that speculative fiction is yet another subset of sci-fi. Both groups are wrong. Speculative fiction is not a disparaging, belittling, or sub-dividing term. It is a catch-all. A short cut. One that we can put to good use. World Weaver Press’s content guidelines are over 500 words long. And that’s just in regards to content — it doesn’t even begin to take into consideration the formatting guidelines and submission methods. Over 500 words to explain where in the river of speculative fiction World Weaver Press stands. It’s a big, wide river. Having a shortcut to describe the whole river instead of always having to refer to it as the current, the rapids, that little slow moving pool off there to the side where the fish tend to gather — is a good thing. Using the term “speculative fiction” also allows us to understand what certain works are when they aren’t overtly in any other category. Stories that do not operate strictly within the known rules of our reality but don’t seem like any other science fiction or fantasy we’ve ever seen — the TV show Lost is a great example of this. When I first came to Lost, I thought it was just a bunch of people shipwrecked on a tropical island — a story that would completely obey the rules of our reality. But it became clear as I watched that this show most certainly did not obey the rules of our reality. It wasn’t like any piece of science fiction or fantasy I’d previously seen, but it was most certainly in possession of speculative story elements. Venn diagram time. The blue of speculative fiction encompasses fantasy, science fiction, the area of fiction where the two overlap, and a bunch of the nebulous space outside of sci-fi and fantasy — dystopia and alternate history, for example. Speculative fiction also encompasses some but not all of the genre of horror.

Much horror is speculative in nature: poltergeists, demonic possession, satanic ritual, viruses that make people into brain-eating zombies, personified-Death coming to get you, aliens bursting out of your stomach and eating you. But horror doesn’t necessarily need speculative elements to be horrifying. Think of the 1973 horror film The Wicker Man. (I’ve not seen the 2006 remake and don’t know how true they stay to the 1973 plot, so let’s go with the older version.) There’s an island of people off the coast of England who lure a detective onto their island, then after an appropriate amount of suspense, they shove him into a giant wicker cage (shaped like a man) and burn him alive. Horror? Definitely. Speculative? Nope, not really. Every single thing they did can be explained by the rules of our reality — no one had magic wands or the ability to travel time or space instantaneously. No demons sprang up from the earth to tell the islanders to kill the detective. They did it because they’d always done it. It was ritual. A horrifying ritual but not one that encompassed any speculative elements.

1 Comment

|

World Weaver PressPublishing fantasy, paranormal, and science fiction. Archives

February 2024

|

- Home

-

Books

-

All Books

>

- Beyond the Glass Slipper

- Bite Somebody

- Bite Somebody Else

- Black Pearl Dreaming

- Cassandra Complex

- Causality Loop

- Clockwork, Curses, and Coal

- Continuum

- Corvidae

- Cursed: Wickedly Fun Stories

- Dream Eater

- Equus

- Fae

- Falling of the Moon

- Far Orbit

- Far Orbit Apogee

- Fractured Days

- Frozen Fairy Tales

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Winters

- Grandmother Paradox

- Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline

- Haunted Housewives

- Heir to the Lamp

- He Sees You When He's Creepin': Tales of Krampus

- Into the Moonless Night

- Jack Jetstark's Intergalactic Freakshow

- King of Ash and Bones (ebook)

- Krampusnacht

- Last Dream of Her Mortal Soul

- Meddlers of Moonshine

- Mothers of Enchantment

- Mrs Claus

- Multispecies Cities

- Murder in the Generative Kitchen

- Recognize Fascism

- Scarecrow

- Sirens

- Shards of History

- Shattered Fates

- Skull and Pestle

- Solarpunk (Translation)

- Solarpunk Creatures

- Solomon's Bell

- SonofaWitch!

- Speculative Story Bites

- Trenchcoats, Towers, and Trolls

- Weredog Whisperer

- Wolves and Witches

- Anthologies and Collections

- Novels

- Novellas

- Fairy Tale

- Fantasy

- Romance

- Science Fiction

- Urban/Contemporary Fantasy

- Young Adult SFF

-

All Books

>

- Blog

- About

- Contact

- Press / Publicity

- Newsletter Signup

- Privacy Policy

- Store

RSS Feed

RSS Feed